Before They Were Parks

Pick any public park, and it has a story to reveal about what it once was and how it came to be. It may be lush and green now, but at some point in its past it might have been a warehouse, tenement, estate, reservoir, landfill, cemetery or jail. The route from private ownership to public amenity is typically long and arduous. Here we feature a fraction of the countless scenarios that have marked the city’s never–ending quest for parkland in a densely built metropolis.

An exhibit on this subject was on display in the Arsenal Gallery from June 23, 2010–September 9, 2010.

Select a borough:

Manhattan

Bleecker Street Playground, Manhattan

The land for this playground in the West Village was once part of the Bleecker family farm, which was ceded to the city in 1809 by Anthony Lispenard Bleecker. The last private occupant of the space was the Stetler Warehouse, owned by businessman Henry Stetler. Stetler made a fortune in the late 19th century warehouse industry, and subsequently lost it during the Great Depression. In 1927 the warehouse was the scene of a sensational rooftop shootout and fire which injured 46 firefighters. An octagonal comfort station immediately to the north, which also once doubled as a bandstand pavilion, was later condemned along with the warehouse to build this park.

In 1959, demand for a safe play space for neighborhood children prodded the city to acquire the Stetler Warehouse south of historic Abingdon Square to make way for a playground, the first in the area. Its development followed the implementation of a new traffic pattern that involved the widening of Bleecker Street and elimination of part of Bank Street. When the playground and sitting area eventually opened in 1966, Parks Commissioner Thomas Hoving, lamenting that community input ought to have been solicited earlier, wryly noted “we would have been spared the years of guerilla warfare over such little but important items as the shape of a bench or a light fixture.”

In 1997, park facilities underwent a large renovation that included new lighting, benches, shrubbery, handicap accessibility, new play equipment and the reinstallation of play equipment that was contributed by the Mollie Parnis Livingston Foundation in 1994. The southern area was slated in 2010 for a renovation that includes improved perimeter plantings and more hospitable seating.

Click on an image to view a larger size and more information

Bryant Park, Manhattan

What is today Bryant Park was used for military drills during the American Revolution before becoming a potter’s field (a burial place for unknown or indigent people) established by the City of New York, from 1823 until 1840. Its use ceased when the Croton Distributing Reservoir was built on the east side of the park between 1837 and 1842, where the New York Public Library built in 1911 now stands. The land of the former potter’s field became Reservoir Square in 1847, and in 1853 the western section hosted the exposition hall known as the Crystal Palace.

The property was designated a park in 1871, and in 1884 the park was renamed Bryant Park for New York Evening Post editor William Cullen Bryant. The reservoir, which was the city’s prime water source for a time, was removed in the 1890s. The park was redesigned in the French style in 1933 by Lusby Simpson, and built in 1934. The park underwent an extensive renovation that began in 1988 by the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, and it fully reopened in 1992.

Click on an image to view a larger size and more information

City Hall Park, Manhattan

City Hall Park has played a key role in New York civic life for centuries, from its colonial beginnings as a rebel outpost to its current function as the seat of New York City government. Used since the seventeenth century as a pasture and then a public commons, City Hall Park has housed, among other things, an art museum, an almshouse, a jail, soldiers’ barracks, a hospital, an African American burial ground, and of course the Tweed Courthouse and City Hall. The park was also once home to the main Post Office, located in the same building as the U.S. District and Circuit Courts. The City Hall Post Office and Courthouse stood at the park’s southern tip from 1878 until its removal in 1938, when this part of the park was renovated in 1939–41. This heavily ornamented structure was extremely unpopular and was commonly known as “Mullett’s Monstrosity,” after designer Alfred B. Mullett. In 1999 a $34.6 million capital project fully restored the park, returning the historical Jacob Wrey Mould fountain to the park and adding a central walkway and gardens and replacing pavement with grass and trees.

Click on an image to view a larger size and more information

Damrosch Park and Lincoln Center, Manhattan

Consisting of neighborhoods that were home to primarily middle– and lower–class Irish and black residents, the areas known as Lincoln Square and San Juan Hill were razed in the late 1950s as part of a large slum–clearance project to make way for a cultural center. Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts opened in 1962, home to many important cultural institutions such as the Metropolitan Opera, New York City Ballet, and New York Philharmonic. Damrosch Park, opened in 1969, was designed by modernist landscape architect Dan Kiley. A current renovation designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro preserves the original buildings and plazas while introducing new amenities and improving the public spaces.

Click on an image to view a larger size and more information

Fort Tryon Park, Manhattan

The densely forested, rocky hills at the northern end of Manhattan were originally inhabited by the Weckquaesgeek Tribe until the early seventeenth century. The early Dutch colonists knew the area as “Lang Bergh” (“Long Hill”). The Continental Army called the strategic series of posts along the Hudson River “Fort Washington” during the summer of 1776, until Hessian mercenaries fighting for the British forced the troops to retreat. The British then renamed the area for Sir William Tryon, the Major General and the last British governor of colonial New York. During the nineteenth century, wealthy New Yorkers built elegant estates around the Fort Tryon area, the most notable being the house of Cornelius K.G. Billings, a wealthy horseman from Chicago. The Billings Mansion burned down in 1925, and the land was donated to the city 1931 by John D. Rockefeller, who bought the estate years earlier. The city designated it as parkland in the same year. The park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., the son of the co–designer of Central and Prospect Parks. Fort Tryon contains some of the highest points in Manhattan and many spectacular views, and is home to the Cloisters which opened in 1938 and is now part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Frederick Douglass Circle, Manhattan

Located at the northwest corner of Central Park at West 110th Street and 8th Avenue, this traffic circle and pedestrian plaza was named in 1950 for abolitionist, statesman and orator Frederick Douglass. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries this spot between Harlem and Morningside Heights was famous for the “suicide curve” of the Ninth Avenue IRT elevated line. At this location, the “El” was over a hundred feet above street level and made two ninety–degree turns. After the demolition of the elevated line in 1940, the intersection was largely unremarkable, and though improvements were sought for a great while, a plan drawn up in the 1970s was never implemented. Many more designs were proposed over the years and finally a collaborative proposal of Harlem–based artist Algernon Miller and Hungarian–born sculptor Gabriel Koren was selected in 2003. Their design includes a standing bronze portrait of Douglass, a bronze water wall depicting the Big Dipper constellation, and colorful stone seating and paving whose patterns are inspired by traditional African–American quilts. The redesigned circle and memorial opened in June of 2010.

Click on an image to view a larger size and more information

High Line, Manhattan

In 1934 the New York Central Railroad opened the High Line, an elevated freight rail that connected Manhattan’s West Side yards at 34th Street to St. John’s Terminal at Spring Street in SoHo. From 1935 to 1937 the Parks Department leased from the New York Central Railroad four lots underneath the High Line, where the department developed playgrounds in this “densely populated” neighborhood where “warehouses and tenements prevail[ed].”

Until its closure in 1980, the High Line ran through commercial districts of Chelsea, the meat market district of the West Village, and Bell Laboratories. The elevated tracks sat dormant and became overrun with a wide variety of plants, visited only by photographers and urban explorers. Park advocates, inspired by the inadvertent meadow the High Line had become, lobbied for its conversion into a public park. The conversion of an elevated railway into a park had been done only once before, at the Promenade Plantée in Paris. The new park, which opened in the summer of 2009, was designed by James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, with planting designer Piet Oudolf. Their design recreated the natural landscape that had formed on the tracks, and recalled its former use by reusing the rails of the abandoned freight line, while making it safe and enjoyable for public use.

Click on an image to view a larger size and more information

Inwood Hill Park, Manhattan

Before becoming parkland, Native Americans known as the Lenape (Delawares) inhabited the area that is now Inwood Hill Park. Through the seventeenth century the area was known during the Colonial and post–Revolutionary War period as Cock or Cox Hill, which is possibly a variant of the Native American name for the area, Shorakapok, meaning either “the wading place,” “the edge of the river,” or “the place between the ridges.” The origin of the current name is unknown.

In the 1800s much of present–day Inwood Hill Park contained country homes and philanthropic institutions. There was a charity house for women, and a free public library (later the Dyckman Institute) was formed. The Straus family (who owned Macy’s) enjoyed a country estate in Inwood; its foundation is still present. When the Department of Parks bought land for the park in 1916, the buildings on the property were demolished but the natural salt marsh was saved and landscaped. A portion of the marsh was later landfilled, though today the park contains the last natural forest and salt marsh in Manhattan. During the Depression the City employed WPA workers to build many of the roads and trails of Inwood Hill Park. In 1995 the Inwood Hill Park Urban Ecology Center was opened, which provides information to the public about the park’s natural and cultural history. Today the Urban Park Rangers work with school children on restoration projects to improve the health and appearance of the park.

James J. Walker Park, Manhattan

The land this park now occupies was acquired in 1705 by Trinity Church as part of a land grant from Queen Anne of England. Trinity operated the site as St. John’s Burial Ground from 1806 to 1842. When the City forbade burials below Canal Street in 1828, St. John’s became Trinity’s main cemetery until it reached capacity and the church opened a new cemetery in upper Manhattan. The city acquired the land in 1895, and the remains were reinterred in the new uptown cemetery, though there is evidence that a portion were not moved. Originally called St. John’s Park, the name was changed to Hudson Park before it opened in 1898 and was renamed again in 1947 after the colorful politician James J. Walker. The original park and pavilion were designed by Carrere and Hastings, architects of the main branch of the New York Public Library. The pavilion was demolished in 1946 to make way for a sandlot baseball diamond, one of the few recreations in a community to this day underserved by recreational facilities. The park underwent renovations multiple times between 1972 and 2008 (1994, 1996, 2000, 2008) to better serve the community’s needs by installing play equipment and other recreational facilities.

Click on an image to view a larger size and more information

Jefferson Market Garden, Manhattan

Today home to a park and library, the Jefferson Market opened on this site in 1833 alongside a police court, a volunteer firehouse, and a jail. The market grew rapidly to include fishmongers, poultry vendors, and hucksters until it was razed in 1873 to make way for a new civic complex and courthouse, which opened in 1877. In 1927 the jail, the market, and the firehouse were demolished and replaced by the city’s only House of Detention for Women, which opened in 1931. Famous residents of the detention center included Mae West, Ethel Rosenberg, and Grace Paley. The adjacent old courthouse was abandoned in 1945, nearly demolished but saved by the Greenwich Village Association in 1962 and readapted as a public library. In 1973 the House of Detention was torn down to make way for a park, its design and care trusted by the city to the Jefferson Market Garden Committee. The garden was originally landscaped by noted horticulturist Pamela Berdan, and today is sustained by volunteers from the community.

Click on an image to view a larger size and more information

Swindler Cove Park and Sherman Creek, Manhattan

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries this area along the Harlem River between Harlem and Inwood was known as “Scullers’ Row,” and it rivaled Philadelphia’s “Boathouse Row” in both size and popularity among rowers. Several dozen boathouses lined the river, many of which relocated from sites along the Hudson River and lower Manhattan waterfronts. In the 1930s, due to encroachment by industry and changing recreational interests, rowing in New York City began to decline and by the 1960s had largely ceased. The area became an illegal garbage dump before environmental educator Billy Swindler, for whom the park was named, brought the site to the attention of the New York Restoration Project, a non–profit organization dedicated to the clean–up and revival of northern Manhattan’s parks. In 1996 the NYRP began a massive clean–up project that removed tons of debris, silt, and toxic waste, and replanted the shoreline with native plant species.

Opened in 2003, the five–acre Swindler Cove Park is situated on Sherman Creek (a tributary of the Harlem River) next to P.S. 5 and includes a community garden and, in the spirit of the site’s past, a boathouse designed by Robert A. M. Stern Architects and architect Armand LeGardeur. Named for the late Peter Jay Sharp, whose foundation was a major contributor to the project, the boathouse is operated by the New York Rowing Association which provides instruction to middle and high school students as well as the general public.

Click on an image to view a larger size and more information

Time Landscape, Manhattan

In the 1950s the buildings on this block were demolished as part of a projected highway construction project that ultimately never went forward due to community opposition. In 1965, conceptual artist Alan Sonfist proposed a series of artworks on vacant lots. His goal was to reestablish the naturalized forest of Manhattan that existed prior to European settlement, to be presented in three stages of forest growth. After extensive research, the planting was completed in 1978, though due to the nature of this landscape, it is ever–changing. While numerous manmade features such as buildings preserve the history of eighteenth–, nineteenth–, and twentieth–century Greenwich Village, Time Landscape serves as a natural landmark of prior centuries.

Click on an image to view a larger size and more information

Washington Square Park, Manhattan

Named after George Washington, Washington Square Park once was a marsh fed by Minetta Brook before serving as a potter’s field or pauper’s burial ground from 1797 to 1826. It is said that while a potter’s field, Washington Square was once the site of a public execution, giving rise to the tale that the Hangman’s Elm that still stands in the northwest corner of the park was once used for hangings. The site was used as the Washington Military Parade Ground in 1826, and became a public park in 1827. Soon after the creation of the Department of Public Parks in 1870, the square was redesigned and improved by M.A. Kellogg, Engineer-in-Chief, and I.A. Pilat, Chief Landscape Gardener. The marble Washington Arch was built between the years 1890 and 1892 to replace the popular wooden arch erected in 1889 to commemorate the centennial of Washington’s inauguration. Use of public space in Washington Square Park has also been redefined throughout the twentieth century. Fifth Avenue ran through the arch until 1964 when the park was redesigned and closed to traffic at the insistence of Village residents. With the addition of bocce courts, game tables, and playgrounds, the park has become an internationally known meeting ground for students, local residents, tourists, chess players, and performers.

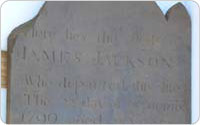

A playground renovation was completed in 1995, and the famous arch restored in 2003-04. In 2009 the first phase of a comprehensive park renovation was completed including the northwest quadrant of the park as well as the central plaza and fountain. During the second phase of the park’s restoration a grave marker was unearthed east of the Arch. Dating to 1799, the tombstone commemorates James Jackson, an Irish immigrant who died of yellow fever, and is one of the few vestiges of the pre-park use of Washington Square as a burial ground.

Related Links

Parks History Historical Signs Capital Projects Park of the Month