Olmsted–Designed New York City Parks

Frederick Law Olmsted buffs and novices alike can benefit from the study of his influence on the New York City parks system.

A Visionary Finds His Way

Although Frederick Law Olmsted (1822–1903) is considered one of America's pioneer landscape architects, he came to the profession only after experimenting and dabbling in many different fields. A newspaperman, social commentator and sometime farmer, Olmsted had many interests early in life. In landscape architecture, he combined his interest in rural life with a sense of democratic idealism to create a new kind of civil engineering that synthesized function and beauty.

The era in which Olmsted grew up was transformative for the country–urbanism and industrialism increasing steadily through the middle part of the 19th century. As the U.S. became more urbanized and more people moved to the cities, reformers and elite thinkers recognized the need for city dwellers to somehow keep nature at hand. Although it may seem obvious, Parks developed only when open space diminished. Olmsted himself straddled the territory between a rural and urban existence. Although he was born in Hartford, Connecticut and attended Yale (before dropping out due to an eye ailment), he spent considerable time in his early adult life on Staten Island when his family purchased a farm for him in 1848. (The site, at 4515 Hylan Boulevard, was acquired by Parks in 2006 and will become Olmsted–Beil House Park.) When his farming experiment failed, Olmsted began traveling in Europe and the American South.

Observing and Absorbing on the Road

The urbanization Olmsted witnessed on the road, along with his interest in rural issues, informed his later work as a landscape architect. While touring Britain in 1850, Olmsted visited England's Birkenhead Park; it was a visit that proved influential in his eventual career path.

Birkenhead Park–one of the first open spaces established by the British government–made such an impression on Olmsted that he submitted a piece in Andrew J. Downing's Horticulturalist about the park, which Downing published in the context of building public support for the concept of Central Park. Downing became a key advocate for Central Park, and in 1850, he introduced Olmsted to a young architect he recruited from England, Calvert Vaux, beginning a decades–long professional relationship between the two designers.

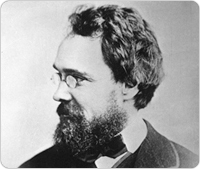

The Other Half: Calvert Vaux

English architect Calvert Vaux (1824–1895) spent 40 years of his distinguished career in New York City, designing private homes, public institutions such as the American Museum of Natural History and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and many parks in the city's parks system. Vaux came to the United States after being recruited by Andrew Jackson Downing (1815–1852) to join his landscaping business based in Newburgh, New York. Downing, one of the main proponents of Central Park, introduced Vaux to Olmsted after Olmsted wrote a piece in Downing's Horticulturalist journal. When Downing died on the steamboat Henry Clay on July 28, 1852, Vaux took over Downing's landscaping company until 1856 when he moved to New York City and began working on the design for Central Park. Through a series of fortunate coincidences, Olmsted acquired the position of Superintendent of Construction of Central Park in 1857. Vaux and Olmsted worked together on the eventual design for the park, now known as the Greensward Plan, beginning the partnership that generated the designs for Central Park and Morningside Park in Manhattan, and Prospect Park and Fort Greene Park in Brooklyn, among others.

The Park That Built the Man

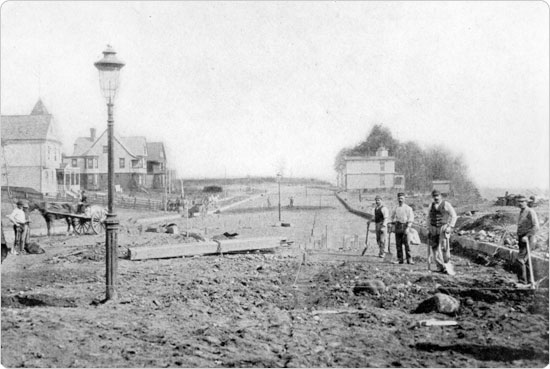

After the New York State Legislature approved the establishment of Central Park in 1853, the Commissioners of the Board of Central Park began the long process of building it. Through family connections, Charles Elliot, a commissioner on the Central Park board, encouraged Olmsted to apply for the position of Central Park superintendent. Thanks in part to Elliot's support, Olmsted was appointed superintendent in 1857.

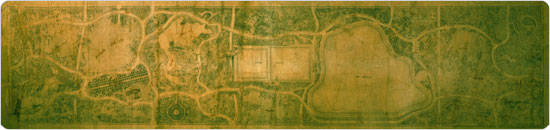

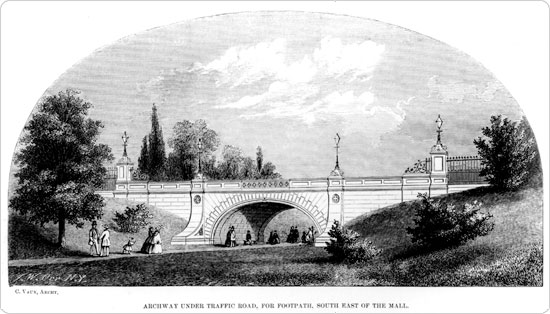

Olmsted began working with Calvert Vaux on Vaux's ideas for Central Park in 1857, and in April 1858, Olmsted and Calvert Vaux submitted the Greensward Plan, one of 33 submissions being considered, to the board. The Greensward Plan, now in the collection of the New York City Municipal Archives, is notable for the way it combined formal and naturalistic settings with architectural flourishes like Bethesda Terrace and the ornate bridges that circulated traffic through the park.

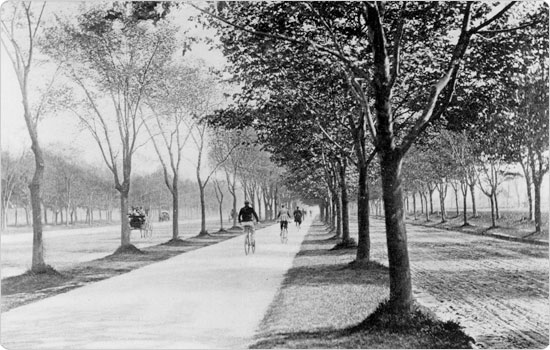

Perhaps most importantly, Olmsted and Vaux's plan for the park created ways for pedestrians and carriages to enjoy the park without disturbing each other. The design's transverse roads, considered revolutionary, allowed vehicular traffic to cut through the park without substantively detracting from the park experience. After the Greensward Plan was adopted, Olmsted was appointed Chief Architect of Central Park.

Olmsted & Vaux Reunited

After a detour during the first years of the Civil War when he served as the executive secretary of the United States Sanitary Commission (a precursor of the Red Cross) and later work for mining interests in California, Olmsted returned to New York in 1865 to collaborate with Vaux on what many consider their most successful design–Brooklyn's Prospect Park.

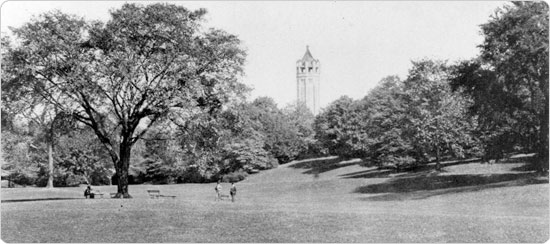

Prospect Park continued the designers' interest in combining formal elements, such as the Concert Grove, with pastoral features, such as the Long Meadow, with rugged rustic elements, like the Ravine. Where design–wise Central Park had several major obstacles to accommodate–its relatively narrow shape and the large reservoir in the center of the park–Olmsted and Vaux were able to take full advantage of Prospect Park's natural elements, including old–growth forests.

Olmsted and Vaux created designs for several other Brooklyn parks including Washington Park (1867, now Fort Greene Park), the Parade Ground, and Tompkins Square (1870, now Von King Park) in Bedford–Stuyvesant. Tompkins Square took the idea of a town square and modified it to account for maximum sunlight and safety; large trees were planted in the center of the park, which was ringed by ornamental gardens.

From Parks to Parkways and Back

Olmsted and Vaux also created designs for a new type of roadway that counteracted against the inefficiency of Brooklyn's grid street system. Olmsted and Vaux called the wide, landscaped roadways they designed "parkways" and used them to connect suburban neighborhoods to the borough's main park, Prospect Park. Eastern Parkway originated near the Queens border, and Ocean Parkway connected Prospect Park's southern boundary with the waterfront at Brighton Beach.

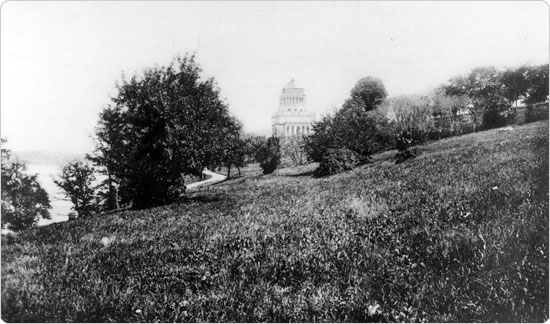

Olmsted and Vaux collaborated on several other projects in the New York City area, including plans for Morningside Park (preliminary plans date to 1873) and Riverside Park (preliminary plans date to 1875). Olmsted's plan for Riverside Park combined elements of the topography–including the parkway that ran through the area–to take advantage of the site's hilly bluffs. Although the park was developed under a succession of landscape architects over the next 25 years, including Samuel Parsons and even Olmsted's partner, Vaux, the English–style rustic park with informally arranged trees and shrubs, contrasting natural enclosures, and open vistas shows Olmsted's touches.

Parks & Politics

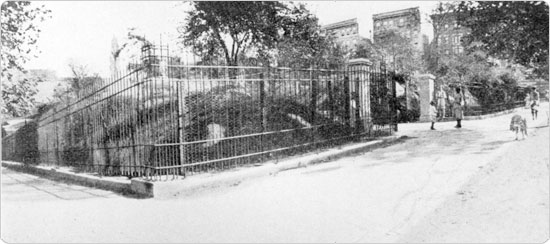

The case of Morningside Park illustrates Olmsted's sometimes complex relationship with the Parks Department. After the Board of Commissioners for Public Parks rejected the design proposals submitted by Parks Engineer–in–Chief M.A. Kellogg in 1871, Olmsted and Vaux submitted a plan in 1873 that was also rejected. Architect Jacob Wrey Mould was hired to rework Olmsted and Vaux's plans in 1880. Mould died in 1886, and 14 years after their original proposal was rejected, Olmsted and Vaux were rehired in 1887 to continue improvements to Morningside Park. The plan enhanced the park's natural elements by planting vegetation tolerant of the dry, rocky environment.

Olmsted was often caught in the middle of political situations. When he applied to the position of superintendent of Central Park, his Republican Party affiliation was seen as a plus by a park board appointed by a Democratic administration that needed a token Republican to satisfy opposition demands. And although he was apolitical when it came to local party politics, Olmsted found himself at the mercy of volatile New York State and City politics during his career. The designer was purged during the short time that Tammany Hall shook up the Central Park board in 1870.

After a debate over the administration of Central Park, he tendered his resignation in 1873, but was forced to reconsider after the depressed economic environment of 1873. In 1878, he lost his job as in–house landscape architect at the Parks Department but was retained on a per–project basis as a consulting landscape architect, a demotion.

Finally, as his association with New York City parks continued to decline, Olmsted relocated to Brookline, Massachusetts in 1883. Soon after, he began working on Boston's Emerald Necklace park system, one of his largest projects.

A National Legacy

Olmsted's legacy can be seen across the country. The Buffalo, New York park system, the US Capitol grounds in Washington, DC, the 1893 Columbian Exposition grounds in Chicago, and Mont Royal Park in Montreal, Canada are just a few of his major works.

In 1895, in poor health and suffering from dementia, Olmsted was committed to McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts, the grounds of which he actually helped design. Frederick Law Olmsted died in 1903.

Beyond the remarkable designs for parks, parkways, country estates, campuses and planned communities that survive to this day, Olmsted's legacy was carried on well into the 20th century by the firm of Olmsted, Olmsted and Eliot (later Olmsted Brothers), which went on to create designs for parks such as Fort Tryon and Sakura Parks in Manhattan, Dyker Beach Park in Brooklyn, and Forest Park in Queens. In 1979, Olmsted's Brookline house (and Olmsted Brothers headquarters) was designated a National Historic Site.

For Further Reading:

The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, ed. Charles E. Beveridge, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1977–1992

- Volume 1 — The Formative Years 1822–1852

- Volume 2 — Slavery and the South 1852–1857

- Volume 3 — Creating Central Park 1857–1861

- Volume 4 — Defending the Union, The Civil War and the U.S. Sanitary Commission 1861–1863

- Volume 5 — The California Frontier 1863–1865

- Volume 6 — The Years of Olmsted, Vaux & Company 1865–1874

- Volume 7 — Parks, Politics and Patronage, 1874–1882

- Volume 8 — The Early Boston Years, 1882–1890

- Volume 9 — The Last Great Projects, 1890–1895

- Supplementary Series Volume 1 Writings on Public Parks, Parkways, and Park Systems

- Supplementary Series Volume 2 Plans and Photographs of Public Parks, Recreation Grounds, Parkways, Park Systems and Scenic Reservations

- Supplementary Series Volume 3 Plans and Photographs of Commissions for Residential Communities, Academic and Residential Institutions, Government Buildings, Scientific Institutions, Expositions, and Private Estates

Landscape into Cityscape: Frederick Law Olmsted's Plans for a Greater New York City, ed. Albert Fein, Cornell University Press, 1967.

Park Maker: A Life of Frederick Law Olmsted, Elizabeth Stevenson, Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1977; new edition: Transaction Publishers, 1999.

FLO: A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted, Laura Wood Roper, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

Frederick Law Olmsted's New York, Elizabeth Barlow and William Alex, Praeger, 1972.

Related Links

Carroll Park (Brooklyn)

Central Park (Manhattan)

Fort Greene Park (Brooklyn)

Herbert Von King Park (Brooklyn)

Morningside Park (Manhattan)

Prospect Park (Brooklyn)

Riverside Park (Manhattan)

Olmsted Center, Flushing Meadows Corona Park (Queens)