Fort Washington Park

The Daily Plant : Thursday, November 16, 2006

1776: Escape From New York

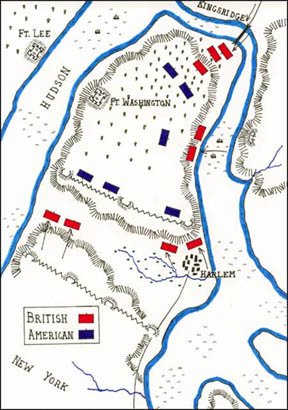

Courtesy of britishbattles.com

It is 20 miles from Gravesend on the southern end of Brooklyn to Inwood on the northern tip of Manhattan. The British Army began its attack on New York in Brooklyn on August 26, 1776, but they did not fully clear the present-day five boroughs of Rebel troops until November 16, exactly 230 years ago today.

Geography? Weather? Luck? Mercy? Historians still argue over how the newest nation on earth went to battle with the greatest nation on earth and somehow survived the encounter. Through a total of nine issues, The Daily Plant has chronicled how the events of the American Revolution that occurred in New York City, tended to take place in land that was then or that would someday become parks. The reasons for these coincidences lie in the fact that both a military general and a park visitor look for the same sorts of amenities: high vistas, waterfront access, and interesting/defensible landscapes that are connected to several modes of transportation.

By November 16 the American forces had already lost the coastlines of Brooklyn, Manhattan, and the Bronx. The British even progressed up through Westchester and most of George Washington’s forces were forced to retreat to New Jersey. One holdout remained, Fort Washington, an area that included two present-day parks. At Manhattan’s highest elevation, these sites represented America’s last stand in New York.

Pennsylvania battalions of the Continental Army began construction for Fort Washington on June 20, 1776. The relatively large complex centered on present-day Fort Washington Avenue and 183rd Street. Although Fort Washington covered a lot of ground, it did not have the stone walls and tall turrets we come to think of when someone says “fort.” Also, the quickly assembled, earthen-walled structure had no water supply and no significant barricade to repel attackers. The “fort” relied not on structure but position for defensibility. With views overlooking the Hudson River to the east, the valley of Manhattan as far south as what is now 120th Street, and protection on the north side from Fort Tryon, it had been a useful lookout in the earlier stages of the war. By November 16, 1776, however, the five-month-old Fort Washington would fall.

With British forces already north of Manhattan in White Plains, British reinforcements had to march back down to Kingsbridge to prepare for their final attack. On the night of November 14, the British succeeded in moving 30 floatboats up the East River past Fort Washington, undetected by the Americans. (Aside from the fort itself, obstacles sunk in the Hudson prevented a naval attack from that river.) On the 15th the British forces approached the fort and (consummate gentlemen) asked the Americans to surrender. Colonel Magaw refused the offer, and on the morning of November 16, the fighting began. Tactical details notwithstanding, with 1,000 wounded and 54 dead, Magaw surrendered, realizing that resistance would only result in a bloodbath.

During the British occupation of New York, the Fort bore the name of Wilhelm, Baron von Knyphausen the German general in British service who commanded the attack and who oversaw New York from 1779 to 1780. After the war, vestiges of the Fort disappeared, and the surrounding area became known as Washington Heights. An 1894 Law mapped out the first section of Fort Washington Park, which now stretches from 155th Street to Dyckman Street and from Riverside Drive to the Hudson River. In nearby Bennett Park granite paving outlines the contours of the southern portion of the former fort complex.

So the next time you’re out in the city, at a waterfront park, atop a hill, or climbing up a valley, look around; there’s a good chance you’re tracing the footsteps of history.

Written by John Mattera

QUOTATION FOR THE DAY

“If you haven't got any charity in your heart, you have the worst kind of heart trouble.”

Bob Hope

(1903 – 2003)

Check out your park's Vital Signs

Clean & Safe

Green & Resilient

Empowered & Engaged Users

Share your feedback or learn more about how this park is part of a

Vital Park System

Know Before You Go