History of Zoos in Parks

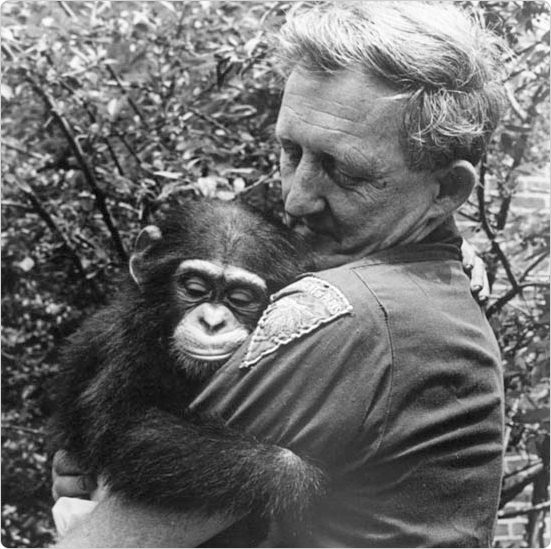

Since early civilization, humans have sought to domesticate and tame animals, and zoos themselves have a long history dating back to the earliest farming cultures. Nearly all of us have visited or still regularly visit zoos, and their unusual position in the continuum between popular entertainment and benevolent conservation (with a significant educational component) makes zoos a fascinating and complex topic. Zoo historian Bernard Livingston explains the dual nature of zoos in the foreword to his Zoo: Animals, People, Places: “Thus the zoo (or menagerie, its original name) has since earliest times been a social phenomenon, a saga of man's inhumanity—or humanity, if you will—to beast, whether for idle pleasure, civic enlightenment or ecological good. The zoo story, accordingly, is a story not only of animals but of the human species as well, and every bit as fascinating as the world of man.” In this way, early zoo proponents were often big game hunters, and zoos themselves often resembled circuses, their inhabitants sometimes anthropomorphized for the entertainment of visitors. Yet just as society has evolved and become more cognizant of its treatment of the planet, and sensitive to its effect on the environment at large, so its zoos have adapted, and the animal habitats in modern wildlife conservation centers barely resemble the stark cages of earlier zoos, except for the fact that people still love to gaze at and study the animals.

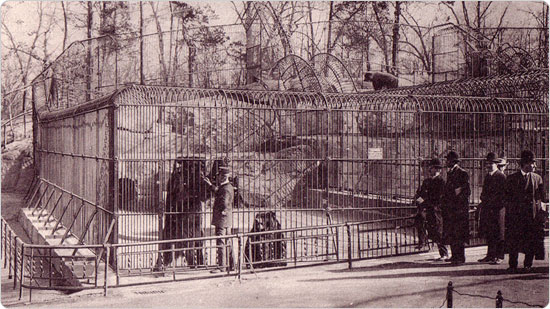

While Philadelphia claims the first zoo chartered in the United States (1859), New York's own Central Park Zoo began as an ad hoc menagerie at the same time, and while Philadelphia's zoo opened in 1874, the menagerie at Central Park was fully institutionalized long before then. In fact, the 1874-75 Report of the Director of the Central Park Menagerie lists page after page of animals exhibited at the park; in that period, seven lions, three pumas, one zebu, and a yak were bred at the menagerie and at the end of 1875, there were 626 animals permanently residing at the zoo.

A professional organization for zoos in New York City dates to 1895 when the New York Zoological Society, the precursor of today's Wildlife Conservation Society, was established. Although the Society's goals have always been the same—to preserve wildlife and inspire New Yorkers and the nation to care for wildlife (the Bronx Zoo, for example, played a key role in reintroducing the American Bison in the early 1900s)—the city's zoos have evolved with the times as professionals have reevaluated how to best care for animals. Where some of the early zoos consisted of little more than cages full of exotic creatures, today's zookeepers spend much more time and effort balancing the dual mission of accommodating a curious public with the need to provide a healthy living environment for the animals.

New York City boasts six zoos—at least one in each borough—and one aquarium, and they are all found in city parks. The zoos feature some of the Parks Department's most artistic and notable art and sculpture, from mid-19th century bronze masterpieces to prime examples of WPA-era art from the 1930s to modern works. Although the city's zoos went through periods of decline over the years, each of the zoos was considered to be an advanced, cutting-edge institution when it debuted (though there is the notorious example of the misguided 1906 exhibit at the then-fledgling Bronx Zoo featuring Ota Benga, a Congolese pygmy). At one time, the Parks Department itself operated three of the zoos—the Central Park, Prospect Park, and Queens Zoos—but after major City-funded capital restorations were undertaken in the 1980s, the Wildlife Conservation Society assumed their management. (The name “Wildlife Conservation Center” was introduced in 1993 to better reflect the institutions' larger goals; the change was derided by language mavens such as William Safire and The New York Times editorial board, which called the new name “multisyllabic mayhem.”)

The shift to a public-private partnership in the operation of the zoos began in the 1960s when two things happened: the formerly “cutting-edge” zoos of the 1930s began to look primitive and outdated, and park administrators needed to divert scarce resources simply to accommodate the basic park needs of a greatly expanded system. The idea to “professionalize” these three zoos became that much more attractive during the fiscal crisis of the 1970s, and by the time Gordon Davis took over as Parks Commissioner in 1978 (and was reportedly embarrassed to go near the dilapidated Central Park Zoo on his way to the Parks headquarters at Central Park's Arsenal), the operation of the city's zoos would soon be out of the Parks Department's hands.

Things got so bad at Central Park that the City-run zoo even lost support of its Friends of the Zoo volunteers. A report jointly prepared by the City and the New York Zoological Society, The Future for New York City's Zoos, identified several reasons that the City was no longer the best entity to run zoos. Severe fiscal restraints were the biggest reason; these left the facilities understaffed and poorly equipped to meet the challenges of running a zoo in an era that went far beyond merely housing an elephant in a cage. In addition, industry standards and even federal regulations became such that Parks administrators (especially at the decision-making upper levels of management) lacked the appropriate training and expertise to run a zoo. Furthermore, being such popular zoos in three major city parks, the institutions deserved modern educational and outreach components that matched their high profile, something far outside the purview of a municipal agency.

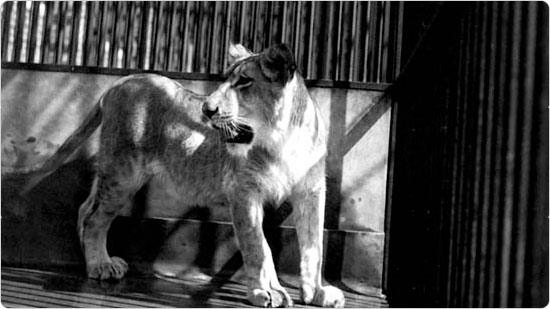

In April 1980, the City and the Zoological Society settled on an agreement that would require the City to renovate the Central Park, Prospect Park, and Queens Zoos, and in return the Society would operate and maintain the facilities. Although the Zoological Society took a more humane approach, the changes dismayed many patrons. Elephants, lions, and other “big game” creatures were no longer on display at the city's smaller zoos and, though slowly, zoo-goers adjusted to institutions that were more about learning and conservation than gawking. Writer Phillip Lopate, in 1990 after touring the new Central Park Zoo, was typical of the sentimentality some felt for the old big game animals: “(T)error-strikers have been banished to the Bronx, and at Central Park we now have a rather gumless collection of birds, seals, polar bears, reptiles, swans, and ants. There is something oddly ‘lite’ about a zoo dominated by creatures of water and air. Even the smells are antiseptic, lacking that nostril-quickening pungency of yore.” (He apparently caught the penguin room on a good day.)

From large game to small fish, the city's zoos succeed in delighting people of all ages while providing cutting-edge research and educational missions.

Further Reading

Bernard Livingston, Zoo: Animals, People, Places, Arbor House Publishing, 1974.

Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park, Cornell University Press, 1998.

Joan Scheier, The Central Park Zoo, Arcadia Publishing, 2002.