War Memorials in Parks

War Memorials are numerous in the City's parks, from modest commemorative plaques honoring solitary soldiers to triumphal arches. More than 270 in number, war memorials account for more than a fourth of all the monuments in our parks.

They are situated in all precincts of the city, from major civic centers to local residential neighborhoods, and they often serve as focal points for civic life in these communities, while honoring those citizens who sacrificed their lives in service of their country. While public and private acts of veneration may take place at these commemorative sites on any day, it is on Memorial Day in the spring and Veterans Day in the fall when these memorials in our midst receive the greatest attention and are the object of public ceremonies, parades, and tributes to the heroic dead.

Memorial Day in New York City

Memorial Day, once known as “Decoration Day,” has been celebrated nationally on the last Monday in May since an act of Congress in 1971, though it has its origins in the post–Civil War era. The first “Decoration Day” was proclaimed by General John Logan, national commander of the Grand Army of the Republic, on May 5, 1868 and was observed later that month on May 30. The first large observance was held that year at Arlington National Cemetery, across the Potomac River from Washington, DC.

In New York City the following year, military regiments and officials massed at Union Square and proceeded to Cypress Hills Cemetery to mark the first local observance of Decoration Day. In 1873, New York became the first state to officially observe the holiday, and by 1890 it was recognized by all of the northern states, though the southern states refused to acknowledge the day, honoring their war dead on separate days until after World War I—when the intent of the holiday was modified to honor not only those who perished in the Civil War, but to honor all Americans who had died in combat. Beginning in the 1880s, the terms “Memorial Day” and “Decoration Day” were often used interchangeably to designate the day on which war dead were honored, with Memorial Day gaining currency especially following the World Wars, and in 1967 the name Memorial Day was made official by Federal law.

This solemn holiday is commemorated in many ceremonies throughout the metropolis from simple wreath layings to parades, the largest of which representing the whole city musters at the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial in Riverside Park. Examples of community-based Memorial Day celebrations include parades in Woodside and Little Neck to Douglaston, Queens, as well as military drills in Clove Lakes Park on Staten Island. The parade in Woodside, celebrated since the 1920s, is sponsored by the Boulevard Gardens American Legion Post No 1836 and St. Sebastian's Catholic War Veterans Post 870. Participants march from the Vietnam War memorial at the intersection of Roosevelt Avenue and 57th Street to Doughboy Park. The Little Neck–Douglaston Memorial Day Parade lays claim to be the nation's largest. Fleet Week, founded in 1984 in New York City coincides with Memorial Day, and includes major festivities at the Intrepid Sea–Air–Space Museum.

Honoring Veterans Day

The day on which we celebrate Veterans Day traces its roots to the moment fighting ended in Europe after the armistice that went into effect on “the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month” in 1918. The next year President Woodrow Wilson adopted November 11 as Armistice Day— a day to commemorate the cessation of what was then known as the Great War, and to honor those who had sacrificed their lives.

Many states made it a legal state holiday, and in 1926 Congress passed a resolution calling for the flag to be displayed on government buildings every November 11. In 1938, Armistice Day was made a federal holiday. At that time the day was more devoted to peace and good will among the nations of the world, but in 1954—following the massive United States war effort in World War II and the subsequent engagement in the Korean War—Armistice Day was changed to become Veterans Day, a day to honor United States veterans of all wars.

The Role of Memorials

For the bereaved, military comrades, and the public at large, the city park memorials function virtually as surrogate graves for those who more often than not died far from the confines of the city, frequently on foreign soil. They are permanent reminders in bronze and stone, as well as landscape art of the steep price our nation, and our metropolis has paid for the preservation of its security and freedoms. While typically erected during the lifetime of those who served or of the families of those who did not return, they have an ability to transcend time, outlasting all with a “living connection,” and their ultimate power is to honor and remind us of the people and events that have helped shape our common history.

Our war memorials provide places of solace and contemplation. Many may be appreciated for their aesthetic and symbolic value apart from their commemorative purpose. Often crafted by leading artists of their day, they complement the mission of the parks in which they reside to sooth the psyche and feed the soul. At their best and when most effective, they connect to a community and cause its citizens to reflect on something larger than themselves.

As with the parks monuments collection in general, the war memorials have in large part not been sponsored by government, but instead created by citizen initiative, and commissioned through private contributions. This process caused neighborhoods to have a stake in their local monuments, and many were dedicated with great pageantry before crowds of enormous size.

With the notable exception of our Revolutionary War memorials, these monuments honor events that took place elsewhere. But though those honored may have lost their lives far from the city, the effects of their loss has brought grief to all communities, to all classes, ethnicities and nationalities, forming a common bond between the citizenry. The stark simplicity of an honor roll listing the names of the fallen local heroes can affect the viewer with a power equal to a more complex and awe-inspiring memorial. It is on Memorial Day and Veterans Day that we pause to reflect on our war memorials—these touchstones of remembrance—and to absorb the deeper message and meaning they convey.

Early War Memorials

Major General James Wolfe

Were it around today, a long-lost obelisk dedicated to the British Major General James Wolfe would be the city's first war memorial. The obelisk was built in 1762 at the end of “Monument Lane” (now Greenwich Avenue) near the present-day intersection of 14th Street and Greenwich Avenue. Wolfe died in the Battle of Quebec, and the obelisk was erected by Oliver de Lancey at the behest of Wolfe's close friend Lieutenant-Governor Robert Monckton. In 1773, the monument no longer appears on local survey maps, though why it was dismantled remains a mystery (some attribute its disappearance to rising anti-Loyalist sentiment, though a more pedestrian explanation may be the reconfiguration of this street intersection).

Worth Monument

The Worth Monument, near Madison Square Park in Manhattan, honors General William Jenkins Worth (1794-1849), who is actually buried beneath the monument. The monument consists of a 51-foot-high obelisk of Quincy granite with decorative bands inscribed with battle sites significant in Worth's military career. The front bears a bronze equestrian relief of Worth, a decorative shield and ornament, and the back supports a large bronze dedicatory plaque. Four corner granite piers (which once held decorative lampposts) anchor an elaborate ornamental cast-iron fence, which has an oak swag motif and whose pickets are replicas of Worth's Congressional Sword of Honor.

Dating to 1857, this site is the second oldest major monument in the parks of New York City. (The George Washington equestrian monument in Union Square claims the honor of first.) After Worth's death in 1849, his body was temporarily interred at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, before being buried on Evacuation Day, November 25, 1857, at the monument's location at the intersection of Fifth Avenue, Broadway, and 25th Street. The Worth Monument was designed by James Goodwin Batterson, who founded Travelers Insurance Company, and was also involved in the design and construction of the United States Capitol and Library of Congress in Washington, D C, as well as the New York State Capitol in Albany.

Revolutionary War Memorials

The American Revolution is the only prolonged military engagement to have occurred within the city's limits, though it would be more than a century before any public memorials to this war were erected.

Battle of Long Island

In Prospect Park, several memorials commemorate the Battle of Brooklyn or Long Island as it is also known, where General George Washington's troops fought British forces during the Revolutionary War. On August 27, 1776 at the “Battle Pass,” a key road that cut through the hills separating the village of Flatbush from Brooklyn and Gowanus, American troops held off Hessian soldiers while the army retreated. A semi-circular bronze marker set within a natural boulder marks the site of the Battle Pass road. In addition, the Dongan Oak Marker, surmounted by a bronze eagle by Alexander Ettl, celebrates a large white oak mentioned in 1685 in the patent of Governor Thomas Dongan (1634-1715) that was cut down by Colonial soldiers and thrown across the road to impede the advance of the British army.

The American troops retreated across what is now Long Meadow, joining troops from Maryland for a final battle near the Old Stone House (now in J.J. Byrne/Washington Park). The bravery of the “Maryland 400” troops is commemorated by a monument at “Lookout Hill” designed by noted architect Stanford White and dedicated in 1895. It consists of a granite column topped by a marble orb and bronze Corinthian capital (the design a recognizable Masonic symbol). The company of soldiers from Maryland held off British General Cornwallis' troops to allow General George Washington and his forces time to escape across Gowanus Creek. The mission was a success, though at a cost of 250 lives; the soldiers are buried at a plot on Third Avenue between 8th and 9th Streets just west of the park. The marble base of the Maryland Monument bears a quotation attributed to General Washington: “My God, What Brave Fellows I Must This Day Lose!”

Learn More: Dongan Oak Monument

Learn More: Maryland Monument

Battle of Harlem Heights

Across the East River in Northern Manhattan, a series of more than a dozen modest monuments from West Harlem to Washington Heights commemorate the Battle of Harlem Heights, which took place in September 1776. The most notable of these is a plaque set within a boulder at the Broadway Mall at 147th Street marking the “First Line of Defense,” and an elegant bronze and granite monument designed by J & R Lamb Company in 1904 set within the rustic wall north of Fort Tryon's Linden Terrace. The former was commissioned by the Daughters of the American Revolution, while the latter was sponsored by the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society and C.K.G. Billings who owned the estate that later became the park.

Learn More: First Line of Defense Marker

George Washington at Valley Forge

This inspirational war memorial represents the Commander in Chief at one of his darkest moments when the Continental Army was encamped at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania in harsh conditions, from which it emerged ultimately triumphant. Sculpted by Henry Shrady, the heroic bronze equestrian sculpture has stood sentinel at the Brooklyn approach to the Williamsburg Bridge since 1906. Shrady, in his first major public commission, chose to depict Washington in a vulnerable pose of contemplation, shrouded in a cloak and hat to protect him from severe weather—a more introspective interpretation than Henry Kirke Brown's equestrian of the commander in Union Square. The large statue was cast at Roman Bronze Works in Brooklyn, and when installed the massive monument required eight sturdy draft horses to transport it and help hoist it into place.

Prison Ship Martyrs Monument

The most impressive Revolutionary War memorial in the city's parks is the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument in Fort Greene Park, which marks not a battle monument but a grave site. The 149-foot-high Doric column designed by architect Stanford White is the site of a crypt for more than 11,500 men and women, known as the prison ship martyrs, who were buried in a tomb near the Brooklyn Navy Yard, just down the hill from Fort Greene Park. The thousands of Colonial soldiers held on prison ships anchored in the East River died of overcrowding, contaminated water, starvation, and disease, and their bodies were hastily buried along the shore. In 1808, these remains were buried in a mass grave on Jackson Street (now Hudson Avenue), near the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and a fraction of these remains were transferred in 1873 to Fort Greene Park. There they were reinterred in 22 boxes in a 25-by-11-foot brick vault marked by a structure designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux (co-designers of Central and Prospect Parks.)

Towards the end of the 19th century, a diverse group of interests including the federal government, municipal and state governments, private societies, and donors, began a campaign for a permanent monument to the prison ship martyrs. In 1905, the architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White was hired to design a new entrance to the crypt and a wide granite stairway leading to a plaza on top of the hill where a Doric column crowned by a bronze lantern was erected. Bronze eagles which mounted on the granite posts at the surrounding plaza's four corners are attributed to Adolph Alexander Weinman. In 1908, the monument was dedicated with great fanfare in a ceremony presided over by President-elect William Howard Taft; a century later, it was rededicated on November 15, 2008, following a restoration of the monument that included completion of certain plaza features never finished originally.

Civil War Monuments

There are about three dozen memorials in our parks related to the Civil War. With the exception of John Quincy Adams Ward's iconic 7th Regiment Memorial (1874) soldier in Central Park and Henry Kirke Brown's statues of President Lincoln for Union Square (1868) and Prospect Park (1869), most were erected at least a generation after the war's conclusion. Another early Civil War monument, the Soldiers Monument (1866) marks the graves of 21 Roman Catholic soldiers in the Union Army and stands on a small plot of land deeded to the City by the trustees of St. Patrick's Cathedral, and today encompassed by Calvary Cemetery.

Many of the finest examples of Civil War monuments in New York's parks honor the commanders of the Union forces: some examples include the Admiral David Glasgow Farragut Monument in Manhattan's Madison Square Park; the General Edward“;Big Ned” Fowler Monument at Fowler Gore in Fort Greene, Brooklyn (Fowler's troops, the “Red-legged Devils of the 14th Regiment who fought heroically at Gettysburg, were bivouacked at was is now Fort Greene Park); the General Daniel Butterfield Statue in Sakura Park on the Upper West Side of Manhattan (in addition to his military service, Butterfield is remembered for composing taps); and the General Philip Henry Sheridan Statue in Manhattan's Christopher Park. In other instances, such as the Soldiers and Sailors memorials at Riverside Park, Grand Army Plaza, and Major John Mark parks, the emphasis is on collective sacrifice during the war that threatened the integrity of the our nation's union.

These Civil War memorials coincide with a flowering of American sculpture. Some of America's best sculptors, working in a “golden age,” contributed pieces to the city. Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907), considered by many as the preeminent sculptor of the Gilded Age of American art, sculpted the Admiral Farragut Monument (1880) located in Madison Square Park, which was his first major public sculpture, as well as the General William Tecumseh Sherman equestrian monument in Manhattan's Grand Army Plaza (1892-1903). Sculptor Frederick W. MacMonnies (1863-1937), who has more than a dozen pieces in New York City parks, contributed monuments of General Henry Warner Slocum (1905) in Brooklyn's Grand Army Plaza, and the Army and Navy groups (1901 and 1902) and Quadriga (1901) on the Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial Arch, also in Grand Army Plaza.

General Sherman Monument

Saint-Gaudens was commissioned to create a monument for General Sherman, of whom he had created a bust in 1888 and with whom he spent much time when Sherman posed for him. Saint-Gaudens's admiration for the general only grew stronger after listening to his many stories; his appreciation for Sherman is evident in the monument's elegant and dignified portrayal of the war hero. For the equestrian monument, Saint-Gaudens labored over every detail of the piece, splitting his time between his studio in Cornish, New Hampshire and Paris, France. The sculptor also became severely ill during the 12 years it took to complete the project, which was one of his last works. As with many of the sculptor's works, the allegorical figure of peace-leading Sherman is modeled after Saint-Gaudens's mistress, Davida Johnson. The pine branch at the horse's feet represents Sherman's march through Georgia.

Disliking statues looking like “smoke stacks,” Saint-Gaudens had the piece gilded with two layers of gold leaf.

Admiral Farragut Monument

Saint-Gaudens' first major public commission, this monument of Civil War Admiral David G. Farragut (1801-1870), considered one of the masterpieces of 19th-century American art, was dedicated in Madison Square on Memorial Day, 1881. Saint-Gaudens collaborated with architect Stanford White, and White designed the elegant base and exedra. Made of Hudson River bluestone, the base fell into such disrepair that in the 1930s, it was replaced with a granite replica, and the original is now displayed at the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish, New Hampshire.

Soldiers and Sailors Arch, Grand Army Plaza, Brooklyn

This grandest of Civil War memorials was designed by John Duncan, architect also of Grant's Tomb. Construction on the Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial Arch began in 1889, and the Arch was dedicated in 1892 at the same time that the architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White began to formalize this entrance to Prospect Park and transform Grand Army Plaza Plaza into a classical space. MacMonnies created the Quadriga (1898) at the top of the arch, the sculptural group The Army: Genius of Patriotism Urging American Soldiers On To Victory (1900) on the left-facing pier, and The Navy: American Sailors At Sea Urged On By the Genius of Patriotism group (1901) on the right-facing pier. Possessing great emotional depth and symbolic power, the sculptural groups are also distinguished by MacMonnies' attention to realistic details of costume and weaponry. The two fine bronze equestrian reliefs of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses Simpson Grant (both 1901) inserted into the interior walls at the base of the arch are by crafted by Thomas Eakins and William O'Donovan (Eakins modeled the horses while O'Donovan crafted the figures.)

Soldiers and Sailors Monument, Riverside Park, Manhattan

This massive circular temple-like monument located along Riverside Drive at 89th Street commemorates Union Army soldiers and sailors who served in the Civil War. It was designed by architects Charles (1860-1944) and Arthur Stoughton (1867-1955), who won a competition with this ancient Greek-styled design. The marble monument, with its pyramidal roof and 12 Corinthian columns, is based on the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens. It was commissioned by the State of New York and dedicated on Memorial Day, 1902. Sculptor Paul E. Duboy carved the ornamental features on the monument. An official New York City Landmark (as with Brooklyn's Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch) the monument has been for decades the terminus of New York City's annual Memorial Day parade.

Soldiers and Sailors Monument, Queens

Located in Jamaica, Queens' Major Mark Park, this bronze angel figure commemorates Union Army soldiers and sailors from Queens who died during the Civil War. The allegorical statue by Alsatian-born and French-trained sculptor Frederic Wellington Ruckstull (1853-1942) contains symbols of victory (the laurel wreath in the left hand) and peace (the palm frond in the right hand)—both common themes of war memorials from the time. Originally located in a nearby street mall, after decades under threat from oncoming traffic, it was relocated to its present, more protected setting in 1960.

Monitor and Merrimac Monument

A stylistic departure from typical late 19th century Civil War sculpture can be seen in the Monitor and Merrimac Monument by sculptor Antonio de Filippo (1900-1993), which was dedicated in 1938 and illustrates a more modern sensibility; the statue depicts a heroic male nude pulling a rope attached to a capstan, and symbolizes Greenpoint-based Swedish-born engineer John Ericsson's role in military-maritime technology while also honoring the memory of the men of the Monitor, who fought an early naval battle against the Confederate Merrimac ship during the Civil War.

Major Clarence T. Barrett Memorial

Unlike the ten bronze portraits of Civil War generals in our parks, the Major Clarence T. Barrett Memorial (1915) by Sherry Edmondson Fry in St. George, Staten Island depicts an idealized classical figure, rather than in military garb, perhaps because the subject went on to distinguish himself equally in local civilian affairs separate from military service.

Cannons

At one time, about 50 cannons and military ordnance serving as artifacts of past wars were displayed in the City's parks, most in small traffic islands. During World War II, most of these were melted down for scrap to support the war effort, except for those examples from the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, deemed of historic value. Today, cannons of Civil War vintage may be viewed in Riverside Park and Brooklyn's John Paul Jones Park, while older cannons and mortars are exhibited at the southwest corner of the Battery and the northeast corner of Central Park. Two Revolutionary War–era cannons are also included in the Fort Greene Park historical interpretive center.

Spanish-American War Memorials

Although it was a short war with a questionable mission, the sacrifice of American troops during the Spanish-American War is also commemorated by several memorials across the city. A column erected in 1919 at Graham Square in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx is dedicated to those from that community who served and died. In 1941, a large granite stele was dedicated to Spanish-American War veterans in Captain George H. Tilly Park in Jamaica, Queens.(Tilly, the son of a prominent Jamaica family, was killed while fighting in the Philippines in 1899.)

Maine Monument

By far, the most significant Spanish-American memorial in the city is the grand Maine Monument (1912) at Central Park's Merchant's Gate at Columbus Circle, that honors the 258 American sailors who perished when the battleship Maine exploded in the harbor of Havana, Cuba, then under Spanish rule. Four days after the Maine went down, newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst's New York Morning Journal called for a public collection to honor the sailors with a monument, and H. Van Buren Magonigle and Attilio Piccirilli were chosen to design and sculpt the massive piece. A bronze figure of a woman, Columbia Triumphant, sits atop the center pylon, riding in a seashell chariot—this group is cast in bronze recovered from the guns of the Maine itself. Allegorical groups adorn the front and side fountains, and the names of those who died on the Maine are inscribed on the pylon above the oceans. The sculptural program figuratively reflects America's new position as a dominant world force, and this imposing Beaux Arts structure, altering this southwest entryway to the pastoral landscape by Olmsted and Vaux, is a bold physical embodiment of this new role on the global stage.

The Hiker

Staten Island's Hiker statue honors local soldiers who served in the Spanish-American War. The statue depicts a foot soldier dressed in military fatigues, with a rifle slung over his shoulder. The image (and nickname) is derived from the long marches that the infantry endured in the tropical Cuban climate and terrain. Several versions of Hiker monuments exist across the country. This one, by Allen G. Newman (1875-1940), was copyrighted by the sculptor in 1904 and for a time served as the official monument of the United Spanish War Veterans (USWV), one of the organizations that that sponsored the Tompkinsville Park monument. One of over twenty Newman Hiker statues cast by J. Williams, Inc., a New York foundry, the pose is thought to be derived from a famous 1899 image by noted American Western artist Frederic Remington (1861-1909), then a war correspondent in Cuba.

World War I Monuments

Encompassing more than 100 different memorials of all shapes and sizes, those park monuments erected in the aftermath of World War I are the most prevalent in New York City parks. This is thanks in part to the massive mobilization that took place all over the country, and the fact that the war marks the first time in American history when huge numbers of American men were called to volunteer for a major war effort abroad. All over the city, neighborhoods commemorated their war dead, often in modest triangles in the center of the neighborhood. Some notable World War I monuments include the Bronx Victory Memorial (1932) in Pelham Bay Park (which is unusual in that it commemorates the entire borough's veterans), Dawn of Glory in Highland Park in Brooklyn, the Pleasant Plains Memorial (1923) in Staten Island, and the Eternal Light Flagstaff in Madison Square Park, the location for the annual Veterans Day citywide ceremony and embarkation spot for the parade up Fifth Avenue.

World War I memorials may be found across the city, from the Astoria Park War Memorial in Queens to the Zion Park War Memorial in Brownsville, Brooklyn, and from the Abingdon Square Doughboy in Manhattan to the Woodlawn Heights War Memorial in the Bronx. One of the most distinctive and recognizable variants of World War I memorials are the so-called “doughboy” statues. The derivation of the term “doughboy” remains in question—it was first used by the British in the late 18th and early 19th centuries to describe soldiers and sailors. In the United States, the nickname was coined during the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and was widely popularized during World War I to refer to infantrymen.

Following the war, in which Americans saw combat in 1917-18, numerous communities commissioned doughboy statues to honor the local war heroes. There are nine such statues in New York City's parks, some examples of which include the Bushwick-Ridgewood Memorial in Brooklyn, the Abingdon Square Doughboy, Chelsea Park Memorial, and Clinton War Memorial in Manhattan and the Woodside Doughboy in Queens (as well as several other examples of Doughboy groups). The doughboy served as a generalized infantryman, in realistic yet heroic poses, that represented the sacrifice of the individual, anonymous soldier—decidedly different in focus from the Civil War monuments that focused on great men in war, instead a poignant self-identification with the youthful everyman. Though all have certain common characteristics, they have a surprising psychological range from combative to pensive.

Abingdon Square Doughboy

The Abingdon Square Doughboy sculpture honors servicemen from the neighborhood of Greenwich Village who died serving in World War I. The dramatic bronze statue on a granite pedestal, dedicated in 1921, is by Philip Martiny (1858-1927), and depicts a foot soldier striding into battle, a gun in one hand while the other carries a swirling American flag. The monument was a gift of the Jefferson Democratic Club, whose headquarters once stood opposite this statue on the site now occupied by the residential high rise at 299 West 12th Street. Martiny received numerous public commissions, among them the statues on the Surrogate Courthouse in Lower Manhattan, and the Chelsea Doughboy at 28th Street and 9th Avenue (for which the same model posed).

Dawn of Glory

A departure in imagery, the allegorical Dawn of Glory in Highland Park was sculpted by Italian immigrant sculptor Pietro Montana (1890-1978), who also sculpted the Freedom Square Memorial (1921) and Bushwick-Ridgewood Memorial (1921), both in Brooklyn. Montana was reported to have used as his model the famous body-builder Charles Atlas (1894-1972). The male figure with face turned skyward in the process of disrobing is the physical embodiment of the spirit of those who served, and the glory in the hereafter. Montana relied on the symbolic power of traditional figurative sculpture, and commented in an address before the Hudson Valley Association, “My wish has been to send light into the darkness of men's hearts, and to be the servant of a noble purpose . . . art is not a vague production, transitory and isolated, but a power, which must be directed toward the refinement and improvement of the human soul.”

Bronx Victory Memorial, Pelham Bay Park

Suitable for a major plaza in the more densely built center city but situated in a bucolic naturalistic setting at the south end of New York City's largest park, the Bronx Victory Memorial was designed by architect and landscape architect John J. Sheridan (1888 -1954 ) and sculptors Belle Kinney(1887-1959) and Leopold Scholz (1877-1946). It consists of a landscaped plaza and a raised paved terrace in which stands a massive limestone pedestal with sculptural reliefs. At the center of the pedestal, a Corinthian column is surmounted by a gilded bronze victory figure. Erected in 1932 and dedicated in 1933, the memorial and adjacent grove of trees on the south side of Shore Road commemorate the 947 soldiers from the Bronx who gave their lives in service during World War I.

The relatively out-of-the-way location of the monument—war memorials frequently being in civic center areas, not large parks on the edge of a borough—is because of a memorial grove that was planted to replace rows of trees planted in 1921 along the Bronx's Grand Concourse, each with a bronze plaque to a fallen soldier, that were removed when the boulevard was widened in 1928. At the behest of several veterans groups, the trees were consolidated into a Memorial Grove between Baychester Avenue and Eastern Boulevard (now Shore Road); these efforts coincided with a plan to erect a unified monument that would honor all servicemen from the Bronx.

The monument's most notable feature is the (Lady of Victory) poised atop a stone globe at the apex of the 70-foot high column. Measuring 18 feet in height and weighing 7,300 pounds, the sculpture and the classical column are part of a long symbolic sculptural tradition dating to Greek and Roman antiquity. The Victory figure on the Bronx Victory Memorial is repeated frequently in monuments throughout the city, the angels purposely beautiful and often holding palm fronds, a symbol of peace, hearkening to the notion that victory in war has a transcendent positive benefit that outweighs the costs in human life.

Pleasant Plains Memorial

The bronze victory figure created by sculptor and Tottenville resident George Thomas Brewster (1862-1943) was originally dedicated on June 9, 1923. Local residents raised funds for the sculpture and commemorative tablets that honor the 493 soldiers and sailors from the Fifth Ward of Staten Island, including the 13 who lost their lives in combat, who served in World War I. The female figure stands on a granite pedestal holding a sword and palm frond high in the air while an eagle with its wings spread sits at her feet. Formerly in a narrower traffic island at the juncture of Amboy and Bloomingdale Roads, the Pleasant Plains Monument was damaged by vehicles in 1968 and 1970. After the second accident, it was removed to storage and at some point it mysteriously disappeared. The present sculpture was recreated from historic photographs and rededicated nearly 74 years later on June 8, 1997.

Eternal Light Flagstaff, Madison Square Park

This monumental flagstaff honors the victorious Army and Navy forces officially received at Madison Square Park following the armistice and the conclusion of World War I. The massive stepped ornamental pedestal, made of Milford pink granite, is inscribed with dedicatory tributes to those who served their country in World War I and lists also the names of significant battle sites. It was designed by Thomas Hastings (1860-1929), whose architectural firm Carrere and Hastings were responsible for many notable buildings, including the New York Public Library. The lavish decorative bronze cap at the base of the flagstaff includes garlands and rams heads and was sculpted by Paul Wayland Bartlett (1865-1925). The monument supports a star-shaped luminaire at the top of the pole, which is intended to be lit at all times as an eternal tribute to those who paid the supreme sacrifice. The monument was dedicated on Armistice Day, November 11, 1923, and each year is the site where the annual Veterans Day parade begins, and official ceremonies are conducted.

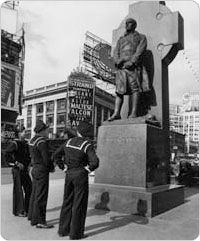

Father Duffy Statue, Times Square

A statue of Father Francis Patrick Duffy (1871-1932), a military chaplain and a priest in the Times Square area, sits at the northern triangle of Times Square, located between 45th and 47th streets, Broadway, and Seventh Avenue. Born in Cobourg, Canada, Father Duffy's military service began in the Spanish-American War of 1898, serving as First Lieutenant and chaplain of the legendary Fighting 69th Infantry of the National Guard, as well as Post Chaplain at the military hospital in Montauk Point, Long Island. In 1912, Father Duffy left St. Joseph's Seminary and moved to New York City to establish the Parish of Our Savior in the Bronx. In 1916, Father Duffy returned to the 69th Infantry, serving in Europe during World War I as part of the Rainbow Division and earning a number of medals.

After the close of the war, Father Duffy returned to New York, and in 1920, was appointed pastor of the Holy Cross Church, located at 237 West 42nd Street. Serving the theater-district community for over a decade, Father Duffy died on June 26, 1932. In 1949, veteran character actor Pat O'Brien portrayed Duffy in the Hollywood film based on his life, The Fighting 69th, which also starred James Cagney. The bronze statue of Duffy by Charles Keck (1875-1951) depicts the priest standing in front of a granite Celtic cross and facing towards his old church. In 2008, a new TKTS booth opened as a backdrop to the statue, featuring a fiberglass shell and a 27-step red glass staircase on which hundreds of visitors may congregate at the heart of the city.

369th Infantry Regiment Memorial

This monument honors the legendary 369th Infantry Regiment, known as the Harlem Hellfighters. The black granite obelisk is a replica of a 1997 memorial that stands at Sechault in Northern France, where the African-American 369th soldiers distinguished themselves during World War I. Unveiled on September 29, 2006, the 88th anniversary of that battle, the obelisk is 12 feet high and features gilded inscriptions, the 369th's crest and its coiled rattlesnake insignia. The monument stands across the street from the 369th Armory, one of the last armories erected in New York City; built between 1921 and 1933, the building is still home to the 369th Sustainment Brigade, as well as historical exhibits and a recreation center.

World War II Memorials

The sheer number of World War I memorials made city officials concerned when thoughts turned to how best to commemorate World War II, in some ways an even larger war. Recognizing that unless some centralized memorials were proposed, the city would not have enough neighborhood spaces to commemorate the World War II effort, officials moved quickly, in fact, before the war ended, to encourage one large-scale monument for each borough.

Brooklyn War Memorial

Following World War II, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses expressed the hope that rather than the disparate group of World War I monuments scattered throughout the parks system, a plan be implemented to erect one consolidated memorial for each borough. The Brooklyn War Memorial was an outgrowth of this plan, and the only borough-wide monument honoring the casualties of World War II to come to fruition. On June 6, 1944, the day US forces stormed the beaches of Normandy, France (D-Day), Brooklyn Eagle publisher Frank D. Schroth formed a committee of distinguished Brooklynites to judge a design competition. The Eagle announced the competition in June, soliciting proposals from a wide array of people. When the contest closed on April 1, 1945, before VE (Victory in Europe) Day, over 243 entries were received. Construction of the memorial began just after Japan surrendered in August 1945.

The memorial in Brooklyn's Cadman Plaza, dedicated on November 12, 1951, consists of a building made of granite and limestone dedicated to the 327,000 American men and women from Brooklyn who served their country during World War II. The memorial was designed by Stuart Constable, Gilmore D. Clarke, and W. Earle Andrews, who worked in concert with the architectural firm of Eggers and Higgins. Today, the memorial serves as a community facility and houses veterans organizations, parks operational personnel (including the monuments field office and shop), and an auditorium with honor rolls.

On the south fa?ade, two larger-than-life sized high relief figures by sculptor Charles Keck (1875-1951) depict a male warrior on the left and a female with a child to the right and serve as symbols of victory and family. Twenty-four feet in height, the sculptures were said, at the time of dedication, to be the largest in New York City. Sculptor Keck is known for his statue of Father Francis P. Duffy (1936) in Manhattan's Duffy Square, the Governor Alfred E. Smith Memorial (1946) in lower Manhattan, and the Sixty-first District Memorial (1922) in Brooklyn's Greenwood Playground.

East Coast Memorial

Located in the southern portion of Battery Park and facing the Statue of Liberty across the harbor, this monument honors more than 4,600 servicemen who lost their lives in the Atlantic Ocean during World War II. It was commissioned by the federal American Battle Monuments Commission, designed by Gehron and Seltzer, and consists of a large paved plaza punctuated by eight massive gray granite pylons on which are inscribed the names, rank, organization, and state of the deceased. In the eastern portion of the plaza a monumental bronze eagle, sculpted by Albino Manca, grips a laurel wreath in its talons, signifying official mourning of those lost at sea. The memorial was dedicated by President John F. Kennedy on May 23, 1963.

Korean War Memorials

Often, the most successful memorials require emotional distance to arrive at a meaningful design. In the case of the Korean War, also known as the “Forgotten War,” several monuments made decades after the conflict were a way of redressing the concerns of those who served in a war that is has often been overlooked.

New York Korean War Veterans Memorial

This monument in Battery Park, north of Castle Clinton, honors military personnel who served in the Korean Conflict (1950-1953). The memorial, dedicated in 1991, was designed by Welsh-born artist Mac Adams (b. 1943) and is notable as one of the first Korean War memorials erected in the United States. In 1987, the Korean War Veterans Memorial Committee was formed to raise money to build a monument to commemorate the soldiers of the “forgotten war.” Adams' winning design, selected from a group of over 100 entries, features a 15-foot-high black granite stele with the shape of a Korean War soldier cut out of the center.

Also known as “The Universal Soldier,” the figure forms a silhouette that allows viewers to see through the monument to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. Adams also designed the piece to function as a sundial; every July 27 at 10:00 a.m., the anniversary of the exact moment in New York when hostilities ceased in Korea, the sun shines through the soldier's head and illuminates the commemorative plaque installed in the ground at the foot of the statue. One of the three tiers in the base of the monument is decorated with a mosaic of flags of the countries that participated in the U.N.-sponsored mission. The plaza's paving blocks are inscribed with the number of dead, wounded, and missing in action from each of the 22 countries that participated in the war.

The Anguish of Experience

One of the most recent war memorials erected in the City's parks, this complex sculpture honors the 172 natives of Queens who gave their lives during the Korean War. Located at the end of a formal allee in Kissena Park, the sculpture by William Crozier consists of a larger-than-life solitary soldier marching on steep and rough terrain. Dressed in military fatigues and clutching his gun across his body, the soldier's face conveys the intensity and hardship of battle. A secondary component creates the illusion of soldiers aiding a wounded comrade in the distance, and an honor role of those who died may be found on the back. The entire monument is framed by prairie grass, symbolizing the soldiers? return, and an asymmetric pattern of granite paving stones, symbolizing the rice fields of Korea.

Vietnam War Memorials

If the Korean War was all but forgotten for a time, the Vietnam War caused deep societal rifts among the nation's people over its mission and purpose. It would not be until the 1980s that the first monuments were created to commemorate a war which many had opposed and towards which others held ambivalent feelings.

These newer monuments are more nontraditional in style and format and expand the educational purpose of the war memorial beyond sheer symbolism.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Manhattan

On May 4, 1985, Mayor Edward I. Koch dedicated Vietnam Veterans Plaza in honor of the 250,000 men and women of New York City who served in the United States armed forces from 1964 to 1975, especially those 1,741 who died fighting the Vietnam War. Beginning in the early 1980s, Mayor Koch campaigned for a memorial to honor those who fought and died in Vietnam. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial Commission raised $1 million from private donations to finance the memorial, as well as to provide counseling and employment services for Vietnam veterans. In 1982, a mayoral task force selected Jeannette Park as the future site for the memorial, and the property was renamed by a local law which Mayor Koch signed that year.

The winning design, by architects Peter Wormser, William Fellows, and writer/veteran Joseph Ferrandino, is a wall of translucent glass blocks on which are engraved excerpts of letters, poems, and diary entries written by men and women of the armed forces, as well as news dispatches. A granite shelf runs along the base of the monument, where visitors leave tokens of remembrance, such as baby shoes, military patches, pictures, plaques, candles, and American flags.

In 2001, the monument site was modified in a renovation designed by E. Timothy Marshall & Associates and Jeffrey S. Poor Landscape Architects. This redesigned plaza now guides visitors through the site with a series of features that educate and inform—an etched stainless-steel map that provides a geographical perspective of the war and details battle zones in South Vietnam greets visitors. A “Walk of Honor,” a series of twelve polished granite pylons with the names of all 1,741 United States military personnel from New York who died as a result of their service in Vietnam, now leads to the memorial. The restoration also included a new black granite fountain and landscaping to create a more welcoming and contemplative space.

Further Reading

Cal Snyder, Out of Fire and Valor, The War Memorials of New York City, Bunker Hill Press, 2005.