History of Theater in Parks

For almost as long as New York has been a world–class city, theater has been a vital part of entertainment in the metropolis. Historians note theater offerings going back into the 17th century in New York, and as theater grew and evolved—first from Lower Broadway to Astor Place to Union Square and finally to Times Square, where "Broadway" now connotes big musical productions rather than the name of a street—it was inevitable that city parks would also be called upon to offer visitors and residents alike the best in theatrical entertainment. For years, parks have been hosting troupes large and small, from mobile marionettes to the biggest Hollywood stars in Shakespeare in the Park.

The warm summer months that nurture outdoor film screenings and concerts also provide a perfect setting for outdoor theater, allowing directors and thespians to return to theater's roots, when ancient Greeks performed tragedies and comedies out in the open. Even the famous Globe Theatre, which debuted many of Shakespeare's plays, was an open–air venue. So even though it may seem jarring to hear the roar of a jet airplane or the buzz of a helicopter at Shakespeare in the Park, keep in mind that you're participating in a tradition of outdoor theater stretching back well over two thousand years.

Theatrical presentations took place in establishments such as Castle Garden in the Battery in the 19th century, but concerts took precedence in parks like Central Park in its early days. Yet as the Parks Department's cultural offerings rose in importance (as did recreational offerings) alongside that of merely enjoying open space, theater became more of a common occurrence. Technology was also a factor; stage lighting not being easily portable, for example, early "theatrical" presentations tended towards pageants. One large pageant in particular occurred in 1912 in Central Park's Sheep Meadow and brought together 5,000 children from across the city dressed in costumes from around the world. The lighting, 10,000 red, white, and blue lights strung among the trees, was sponsored by the New York Edison Electric Light and Power Company.

WPA–Era Theater in the Parks

During the Depression, the government began to expand all kinds of services to an impoverished city. Federal work relief programs supported the arts, and the city used federal funds (and the democratic spaces that parks were) to bring culture to a wider audience. This was the era of Mayor Fiorello La Guardia reading the Sunday comics to children on the city–owned WNYC radio station. And just as out–of–work musicians played free concerts in parks across the five boroughs, so did actors and theater companies. In 1934, La Guardia tried out a "Portable Theatre Drama" program that produced plays through the Drama Division of the Department of Public Welfare. Five portable stages performed six days a week in each of the five boroughs, 30 sites in all. The first show was Uncle Tom's Cabin at Thomas Jefferson Park in Manhattan, and other park sites that summer included Tompkins Park in Brooklyn, Franz Sigel Park in the Bronx, Astoria Park in Queens, and Silver Lake Park in Staten Island, among many others. (Welfare Department officials estimated that 250,000 people saw Harriet Beecher Stowe's play in the summer of 1934, with crowds ranging from 3,000 to an astounding 18,000 people.)

After the 1934 season, vaudeville and circus players asked to be included in the program, and it was expanded in subsequent years so that people could enjoy productions of Gilbert and Sullivan's The Pirates of Penzance in Brooklyn's Owl's Head Park and vaudeville acts in Staten Island's Silver Lake Park. WPA officials reported that over 1.8 million people watched portable theater productions in 1935.

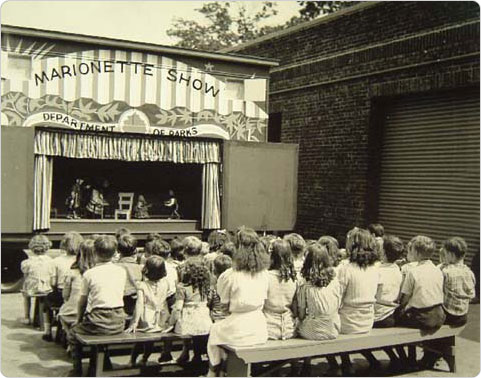

Marionette Theater

In the early part of the 20th century, park advocates bemoaned the "encroachments" on Central Park that threatened Olmsted and Vaux's original vision. A pictorial–editorial published in the New York Times in 1918 illustrated what would have happened "if 'improvement' plans had gobbled Central Park" and noted what it thought to be an ill–conceived and "audacious" suggestion to build an outdoor theater with a capacity of up to 100,000 "at heavy strain to the vocal cords of the actors."

In 1914, the Polish–born vaudeville actress Anna Held suggested that the city build a marionette children's theater in Central Park, similar to the marionette theater in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. Neither plan came to fruition, but by the 1930s, when WPA–sponsored cultural events salved an economically depressed city, marionettes were included in the daily ballet of activities hosted at Central Park and other parks throughout the system. An experiment during Christmas of 1940 with puppet theater expanded into a full summer schedule in 1941. The marionette theater also fit in well with the mission of elevating a populace through arts and culture, especially young people, in order to avoid future social ills. The shows required playground directors to be specially trained in the art of puppeteering, and perennial favorite shows like "Jack and the Beanstalk" excited and thrilled children across the five boroughs.

In 1947, Parks' marionette crew moved into a workshop in the Swedish Cottage in Central Park, and by the 1950s the well–established program was playing hundreds of shows each summer to over 100,000 children each year. Since then, the operation has blossomed into a year–round activity in Central Park, and the theater continues to take its puppets into the boroughs to delight children of all ages. Artistic Director Bruce Cannon has been with the Marionette Theatre since the late 1960s and is himself quite an institution, working with puppeteers not only to produce shows but also craft the puppets used in the shows.

Watch a video about Swedish Cottage Marionette Theater

Current Programs

Children's theater remains an important part of the Parks Department's mission to program parks with cultural and educational activities. Each year, children's theater productions take place across the city, filled with anything from interactive storytelling to clowns and jugglers to more conventional plays.

And let's not leave out adults! Along with the famous Shakespeare in the Park performances, parkgoers can find experimental theater, new works by emerging artists, stand-up comedy, and modern stage classics being acted out throughout the City.

Check out the free theater happening this summer!

Joe Papp and Shakespeare in the Park

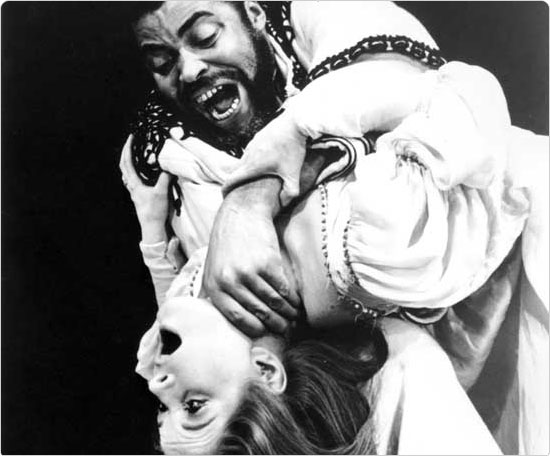

When one thinks of theater in the park, the first thing that probably comes to mind is New York City's Shakespeare in the Park, perhaps the premier example of outdoor theater anywhere. New York theater icon Joseph Papp (1921–1991) founded the Shakespeare Theatre in 1954 to bring the Bard's work to a wider audience. The first production, Julius Caesar, took place in 1956 at the amphitheater in East River Park; until then, the amphitheater hosted the occasional concert but no theater (productions of Greek plays Oedipus Rex and Philoctetes took place at the East River Amphitheater in the mid 1960s before the site was closed in 1973 due to a budget shortage). Papp and his Public Theater began mobile presentations of Shakespeare plays in 1957.

In 1957, Papp and Parks Commissioner Robert Moses battled over whether the Public Theater could use Central Park. The fight took an ugly turn when Moses alleged that Papp had communist links (Papp had refused to admit to the House Un–American Activities Committee whether he was—or knew anyone who was—a communist). Under pressure from the public and Mayor Robert Wagner, Moses eventually relented and allowed Papp to stage free Shakespeare in the park. (The writer Robert Caro pointed to this embarrassing episode as one of the pivotal turning points in Moses' career in The Power Broker.)

Shakespeare in the Park only became more popular when the Delacorte Theatre opened in 1962 in Central Park. The theater's opening performance was The Merchant of Venice, directed by Papp and featuring George C. Scott, James Earl Jones, and William Devane. In 1966, Papp's company bought and began renovating the landmarked former Astor Place Library at 425 Lafayette Street; the conversion of the building was handled by architect Giorgio Cavaglieri, who also designed the Delacorte Theatre.

Other notable Delacorte performances include Much Ado About Nothing (1972) starring Sam Waterston, which began as a Shakespeare in the Park performance, transferred to Broadway, and was subsequently nationally televised on CBS to an audience of millions; The Pirates of Penzance (1980), starring Kevin Kline, which also transferred to Broadway and won three Tony awards; 1991 productions by companies from Brazil and Spain of A Midsummer Night's Dream and The Tempest in Portuguese and Spanish; The Seagull (2001), a piece produced during a tenuous time for film actors amidst possible labor strife (with no major productions scheduled to film during summer of 2001, a stellar group of actors including John Goodman, Marcia Gay Harden, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Meryl Streep, Christopher Walken, Natalie Portman, and Kevin Kline, all directed by Mike Nichols, decided to spend their summer performing for fans who in some cases lined up almost a day in advance for tickets); and Mother Courage (2006), in which George C. Scott directed Meryl Streep in the starring role alongside Shakespeare in the Park regular Kevin Kline.

Watch a video about Shakespeare in the Park

Central Park's Shakespearean Connections

- In 1890, Eugene Schieffelin released 80 starlings into the park, because they were mentioned in Shakespeare's plays (there are now over 200 million of them in America).

- In 1915, the Shakespeare Society assumed maintenance of a rock garden, built in 1912, in the park near West 79th Street.

- In 1934, the Shakespeare Garden, which features species named in his works, was relocated to the hillside between Belvedere Castle and the Swedish Cottage, and in 1989, a new landscape design by Bruce Kelly and David Varnell was implemented.

- A mulberry tree, said to be nursed from a cutting from a tree in Shakespeare's own garden, was planted in the early 20th century with great fanfare in Shakespeare Garden; there were many such cuttings around at that time, and it was determined later to have been a fake.

- In 1958, after two seasons at the East River Amphitheater, Joseph Papp's Shakespeare Festival moved to Central Park; the Delacorte Theater, its permanent home, opened in 1962.

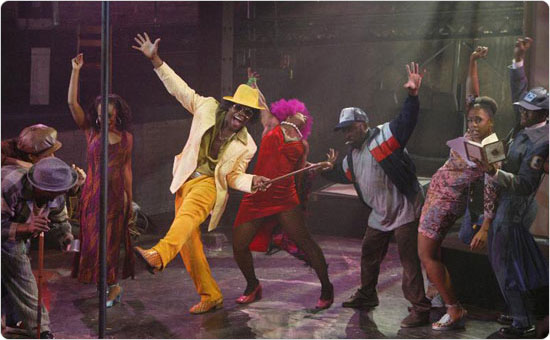

Queens Theatre in the Park

Making its home in the "Theaterama" of the Philip Johnson–designed 1964–65 World's Fair–era New York State Pavilion in Queens' Flushing Meadows Corona Park, the Queens Theatre in the Park has been used as a venue since 1972, a time when the park was undergoing its transformation from World's Fair site to public park. In 1979, New York Times critic Richard F. Shepard noted the joys and exoticness of watching theater in the park while reviewing a Playwrights Horizons performance of Noel Coward's Private Lives: "Noel Coward wrote his comedy Private Lives in 1930, when Queens was still a trip to the country. He probably never dreamed that the play would live on, most charmingly, nearly a half–century later in a theater in something called Flushing Meadow–Corona Park, an area once placed in the minds of sophisticates in the same category of remote outposts of empire as Uttar Pradesh or Zanzibar. This is not to belabor a point, but merely to point out to provincial New York theater goers that a trip to the other boroughs can often bring rewards."

In 1993, the Queens Theatre in the Park was renovated at a cost of $4 million, overhauling its 464–seat main stage theater and a 99–seat studio theater. Today, with 400 annual performances, the theater reaches nearly 100,000 theatergoers. The facility is currently undergoing a $20.45 million renovation that will add a 75–seat cabaret performance space and a new 3,000–square–foot lobby/reception area.

Watch a video about New York State Pavilion in Flushing Meadows Corona Park

One–Off Events

For years, artists have been producing one–off theater productions in city parks. In cooperation with Mayor John V. Lindsay's Summer Task Force program and the Parks Department, the Puerto Rican Traveling Theater performed Rene Marques' The Ox Cart in 1967 at the Casita Maria Carver Amphitheater on 102nd Street between Park and Madison. In 1989, Anna Hamburger and En Garde Arts produced a "Plays in the Park" trilogy that used locations in Central Park, including Bow Bridge, Belvedere Castle, and the lawn next to the Dairy. In 2009, parkgoers saw Joan of Arc, as presented by Gorilla Rep; the Piper Theatre Company's version of Rosencranz and Guildenstern Are Dead; and the Inwood Shakespeare Festival's production of Dracula; among other unusual performances.

Theater–Related Sculptures

William Shakespeare, Central Park

A full–standing portrait of celebrated playwright and poet William Shakespeare (1564–1616) was made by John Quincy Adams Ward (1830–1910) and unveiled on Central Park's Literary Walk on May 23, 1872. Coinciding with the tricentennial of Shakespeare's birth, a group of actors and theatrical managers, among them noted Shakepearean actor Edwin Booth (1833–1893), received permission from Central Park's Board of Commissioners in 1864 to lay the cornerstone for a statue at the south end of the Mall between two elms. Delayed by the end of the Civil War, Ward was selected by a competition in 1866, and the committee raised funds through several benefits, including a performance of Julius Caesar. Jacob Wrey Mould, chief architect for parks at the time and responsible for much of the ornament and architecture in Central Park, designed the elaborate pedestal for this statue.

Romeo and Juliet & The Tempest, Delacorte Theatre, Central Park

Sculptor Milton Hebald (born 1917) created these companion pieces depicting both the doomed lovers in Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet and Prospero, one of the main characters in The Tempest. The bronze statues were gifts of philanthropist George T. Delacorte (1894–1991), who also donated the Delacorte Theater, which the two works of art stand in front of. The theater is best known for its free Public Theater productions that play each summer and feature at least one Shakespeare classic.

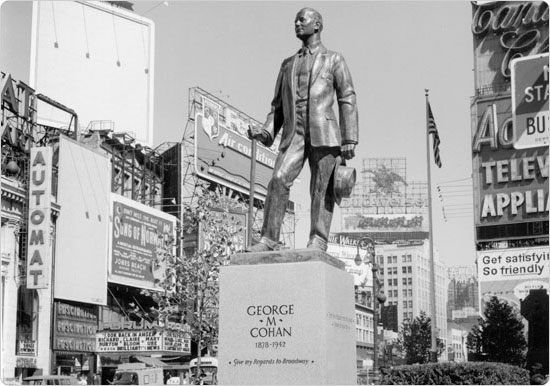

George M. Cohan, Duffy Square

A bronze statue depicting the American composer, playwright, actor, and producer George M. Cohan (1878–1942) designed by Georg John Lober (1892–1961) stands in Times Square's Duffy Square, right in the heart of the Broadway theater district. Dedicated in 1959, the statue's inscription, "Give my regards to Broadway," appropriately quotes Cohan's most famous song. The memorial committee that sought to commission the piece included noted composers Irving Berlin and Oscar Hammerstein II.