History of Recreation in Parks

Since the ancient Greeks (or even earlier) there has been a strong link between physical health and general wellbeing. For nearly 100 years, the Parks Department has been at the forefront in supporting a healthy city and putting the “recreation” in “Parks & Recreation.” From the early bathhouses to the anti–obesity programs of today, the Parks Department's focus on active recreation has supported the goal of a healthy citizenry and positive social and moral conduct.

The Movement's Beginning

The Recreation movement in the United States dates to the social programs of the late 19th century, and the city's own bathhouses functioned as early recreation centers. A state legislative act in 1895 mandated the construction of free public baths in cities of populations of 50,000 or more and by 1911 twelve public baths opened in Manhattan. Many of Parks' current recreation centers were originally bathhouses, including Hamilton Fish (opened in 1900), Asser Levy (opened in 1908 as the East 23rd Street Bathhouse), Tony Dapolito (opened in 1908 as the Carmine Street Bathhouse), Recreation Center Fifty–Four (opened in 1911 as the East 54th Street Bathhouse) and Recreation Center 59 (opened in 1912 as the West 60th Street Bathhouse).

Part of a larger effort to serve overcrowded working–class tenement districts for the purposes of public hygiene and recreation, the ornate architecture of these bathhouses have an uplifting quality and contribute to the sense of purpose with which reformers tackled social problems. The Asser Levy Recreation Center in particular, which was designated an official city landmark in 1974, exemplifies this link. Echoing the style of ancient Roman baths, the architecture was inspired by the “City Beautiful” movement, the turn–of–the–century effort to create civic architecture in the United States that rivaled the monuments of the great European capitals. Originally, these facilities were not under the jurisdiction of Parks (the offices of the Borough Presidents and Department of Public Works administered them), as the link between parks and the goal of supporting a healthy citizenry was not as firmly established.

Reform mayor William Jay Gaynor appointed reform–minded Charles Stover to serve as Manhattan Parks Commissioner in 1910, and the city began to link parks, active recreation, and social progress. Stover had previously worked with Lillian Wald, the director of the Henry Street Settlement, to found the Outdoor Recreation League (ORL), whose mission was to provide play spaces and organize games for the children of the densely populated Lower East Side. The ORL opened nine privately sponsored playgrounds and advocated that the City itself build and operate playgrounds. Stover established the first Bureau of Recreation in 1910, and his tenure was notable for dozens of upgraded and newly built playground sites, and the attention the Parks Department paid to cultural and recreational programs for children, from track meets to folk dancing.

Establishing the office of recreation supervisor was a change pushed by a diverse collection of interests, including various playground associations such as the Outdoor Recreation League and the Public School Athletic League and the National Highway Protective Society—car enthusiasts—who wanted the streets safely clear of children; news reports noted 88 street–related deaths of children age 14 and under in Manhattan and Brooklyn for 1909. “Conscientious autoists, owners, and drivers are continually harried by the fear of running down youngsters who play games on the street, while others are irritated by children dashing in front of their cars,” The New York Times explained. Ideas floated at the time mirrored later innovations in park planning: closing streets to traffic for play areas, opening school yards for play outside of school hours, and transforming vacant lots to play areas.

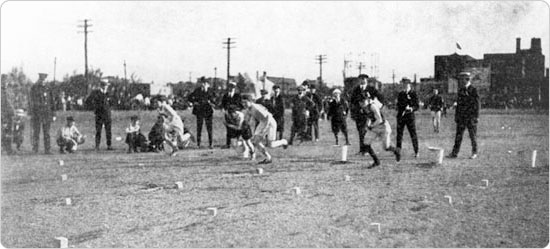

The Lee Era

William J. Lee served as one of the Parks Department's first recreation supervisors, and the program saw immediate results. Lee noted in the 1911 annual report for the department that the “wisdom and correctness of your views in establishing the Bureau of Recreation in the summer of 1910 is justified by the results.” “[S]ustained by the entire press of this city, reflecting popular sentiment,” Lee reported a 100 percent increase in attendance and presented staggering figures: over three million people used the 30 playgrounds under the jurisdiction of the department. Programs were divided between boys and girls, and programming included a “Playground Athletic Championship” between rival parks on Memorial Day, in which 5,000 boys between 7 and 17 competed 16 athletic events. 1,000 medals were awarded courtesy of the New York Sunday World, and a Parks Band playing “patriotic airs” accompanied the boys who performed in front of 10,000 spectators: “No accidents were recorded, and no arrests were necessary . . . There were but five policemen detailed to the scene, and order and discipline prevailed throughout the day.”

Girls participated in “The Parade of the States” festival held in Hamilton Fish Park on July 1, 1911. Participants “[embodied] the songs and dances and costumes in vogue in the various sections of our land,” and each playground was given a particular section of the States to represent, rehearsing songs and dances. “The entire press of the City commended this work as morally, socially, and geographically instructive,” Lee noted. “It was given wide publicity with photographs, and fully seven to eight thousand children and parents witnessed this very excellent performance. After the festival was over, refreshments were served at the indoor gymnasium to the children who participated in the affair. The children were returned to their respective homes by the playground leaders.”

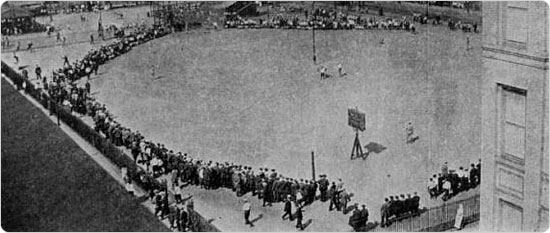

Other programs were similarly successful. The Bureau of Recreation helped promote and run Mayor Gaynor's “Safe and Sane” Fourth of July celebrations, and Parks' athletic grounds were used for the Fourth of July games, which saw 7,000 entrants—Lee perhaps exaggerated slightly when he called it “the largest athletic program in the history of athletics in the world,” but it was not far off. Lee reported 200,000 people witnessed these games. He was no less enthusiastic about the bureau's role in organizing the “largest baseball league in the history of the national game,” 500 teams organized at the playground level with boys age 7 to 17, twelve boys to a team. The New York Herald donated 1,000 medals for the championship rounds. A team from Tompkins Square won the Junior Championships, and teams from Hamilton Fish and Seward Park Playgrounds won the Senior Championships: “The marvel of the situation is that the boys from the most congested downtown centers of the City, where there is practically no baseball area, defeated the boys from the upper section of the City, who have baseball grounds,” wrote Lee. “It would seem that 'There is safety in numbers.'”

Lee reported that playground attendance for 1911 had reached “over a half million monthly” by the summer months and noted the opening of a playground at Colonial Park (now Jackie Robinson) and a donation by New York Herald publisher James Gordon Bennett, Jr. to use land owned by the family for three baseball diamonds at 184th Street and Broadway. Parks also dedicated the West 59th Street Athletic Field, adjoining De Witt Clinton High School. A playground opened at Columbus Park &40;in what was once considered the most dangerous neighborhood in the country) in Lower Manhattan on Columbus Day, October 12, 1911: “The opening of this park playground marked a new era in the 'Italian quarter' of this City,” Lee reported. “This spot, so long idle and neglected, has been transformed into one of the finest boys' playgrounds and athletic fields in the City, facing the old Five Points Mission House.”

Lee went on to quote a report of the National Highways Protective Society showing 43 deaths occurring during the month of September on the streets of New York, of which 30 were children 16 or under, “And yet, while over three million children and adults participated in the festivals and games of the park playgrounds, no deaths have been recorded, and the very few accidents have been of a minor nature. Thus, it is readily seen that the real guardians of the City's children are the playground leaders, and the park playgrounds are the 'Isles of Safety' for the children of New York.”

Lee summed up the work of the bureau in its first full year:

The tone of park playground work has been raised to a higher standard. The smaller children have not been neglected; they have been instructed in jig–saw raffia work and drawing, which give pleasure to those not fitted for strenuous exercise and games. The inter–park games and festivals in “God's out–of–doors” afforded an opportunity to the children to take excursions, accompanied by the playground leaders, from one playground to another, establishing social intercourse, and bringing into the lives of the children a feeling of civic pride and friendly  competition which has not been surpassed. According to the statistics of the Children's Court, there are over 10,000 children arrested annually for trivial offenses. His Honor, Mayor William J. Gaynor, had labored unceasingly to prevent unnecessary arrests of both children and adults. Most of these offenses, if committed in the playgrounds, would not be a violation of law, such as baseball, “cat,” football and roller skating, which is generally an outburst of suppressed energy. The playgrounds furnish play–material for all games under intelligent supervision. It is, therefore, our duty to plan wisely and well for future needs and to protect the best interests of our present and future citizens.

competition which has not been surpassed. According to the statistics of the Children's Court, there are over 10,000 children arrested annually for trivial offenses. His Honor, Mayor William J. Gaynor, had labored unceasingly to prevent unnecessary arrests of both children and adults. Most of these offenses, if committed in the playgrounds, would not be a violation of law, such as baseball, “cat,” football and roller skating, which is generally an outburst of suppressed energy. The playgrounds furnish play–material for all games under intelligent supervision. It is, therefore, our duty to plan wisely and well for future needs and to protect the best interests of our present and future citizens.

The Bureau of Recreation continued the efforts of the department to address the city's recreation needs, and Lee's 1912 report boasted, “The development of the grounds now under course of construction will be an additional gain to playground work in this City. When these facts are taken into consideration that in three years, thirty park playgrounds and recreation centres, varying from little children's playgrounds to athletic fields and baseball grounds and indoor gymnasiums have been developed under your administration, it would seem that this advancement has been unparalleled in the history of the playground movement, and the widespread demand is apparent on all sides to maintain these grounds the year round.”

The Moses Era

Year–round recreation became one of Parks Commissioner Robert Moses' goals after assuming responsibility of a citywide Parks Department in 1934. From the outset, Moses used recreation, along with parkway construction and later housing, as one of the main tools to advance social progress. One of the first items Robert Moses tackled was developing five model playgrounds for children and expanding their hours. The original “model playgrounds” were meant to serve as templates for further playground designs and included standard features such as a play house, flagpole, chlorinated footbath, wading pool, handball and basketball courts, play equipment, drinking fountains, shade trees, and shrubs. The five original model playgrounds were Gertrude B. Kelly Playground at 17th Street near Ninth Avenue in Manhattan, Washington Park at 4th Avenue and 3rd Street in Brooklyn, a playground in Astoria Park in Queens, Zimmerman Playground at Barker Avenue, Britton Street, and Olinville Avenue in the Bronx, and a playground in Clove Lakes Park in Staten Island.

Commissioner Moses' earliest projects illustrate the Parks Department's commitment to recreation. Sara D. Roosevelt Park on the Lower East Side was an early priority, Commissioner Moses announcing plans for the sprawling site in February 1934. In the case of Sara D. Roosevelt Park, tenements cleared and streets closed originally for housing were utilized for playgrounds, a seven–block–long stretch from Canal to Houston streets in one of the densest part of the city.

Parks also got started quickly training recreation staff to facilitate play at the sites. In fact, in the first months of Moses' tenure as citywide Parks Commissioner, large recreation projects across the city were announced: Kissena Park in Queens (March 1934), the adaptation of the former reservoir site in Central Park to become the recreational facilities on the Great Lawn (March 1934), Crotona Park in the Bronx (May 1934), and a massive beach reclamation—and notably, a huge influx of recreation facilities—at Orchard Beach in the Bronx (May 1934).

In Kissena Park, the Parks Department attempted to balance the “informal” nature of the site with recreational facilities for both adults and children, including tennis courts, handball courts, baseball diamonds, football fields, and archery ranges, as well as an 18–hole pitch–and–putt golf course. For Central Park, the scene of battles over the years regarding encroachments to Olmsted and Vaux's design, the Parks Department acknowledged the recreational uses of the North Meadow and sought to formalize the facilities there, screening the spot off from the East and West Park drives and designing it for baseball in the summer months and football and field hockey in the fall months.

Orchard Beach was one of the clearest examples of building recreational facilities for the public good as the Parks Department sought to eliminate the private use of the beaches in favor of opening the site up to the general public: “Up to now one–third of the whole area of Orchard Beach has been preempted as a special privilege for a few hundred campers,” Parks stated. “The new plan provides facilities which will be open without exception to the general public.” The Orchard Beach design was in part based on Robert Moses' Jones Beach work in Nassau County on Long Island, and combined his belief in the future of the automobile (the site had one of the largest parking fields in the city) with a faith in the power of recreation to cure social ills. Orchard Beach provided not only an elegant bathhouse (landmarked in 2007) but also many playgrounds, acres of athletic fields for baseball, football, and soccer, and several tennis courts.

One of the first large public–private initiatives of the Moses administration was the “Learn to Swim” programs at pools across the city in the summer of 1934, which served several thousand adults and children. The new administration also provided day camps for children in the summer of 1934 at Inwood Hill Park in Manhattan, Forest Park in Queens, and Pelham Bay Park and Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx.

The commitment to recreation is perhaps best expressed in the example of the nine “War Memorial Playgrounds” that were built in 1934. The first of hundreds of playgrounds to be built during Moses' tenure, the funding for the nine playgrounds came from a defunct fund to build a memorial arch to commemorate those killed in World War I. When organizers fell short of the $1 million fundraising goal, the money was turned over to the city, where it collected interest in the intervening years. That Commissioner Moses convinced the War Memorial Committee to consent to use the funds for playgrounds is a strong indicator of the link between recreation and the social good.

With additional funding from the Federal Temporary Emergency Relief Administration, the nine playgrounds were constructed in less than four months. Each was equipped with a play area, wading pool, brick field house and comfort station, and flagpole. The legal decision that paved the way for Parks to build the War Memorial playgrounds stipulated that each property be dedicated as a war memorial and contain bronze tablets commemorating fallen soldiers, which exist to this day across the city—two are in Manhattan, two in Queens, two in Staten Island, two in the Bronx, two in Staten Island, and one in Brooklyn. Parks, under Moses' leadership, added nearly 40 playgrounds to the existing 119 in 1934; a 33% increase in one year alone.

Swimming as Recreation

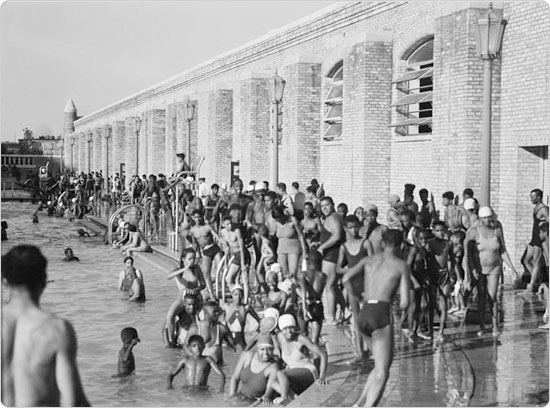

In this era of parks fulfilling recreational goals, polluted waterways were a problem not for wildlife but because no one could use them for swimming. As the Moses administration argued in a press release dated July 23, 1934, “It is one of the tragedies of New York life, and a monument to past indifference, waste, selfishness, and stupid planning that the magnificent natural boundary waters of the city have been in a large measure destroyed for recreational purposes by haphazard industrial and commercial developments, and by pollution through sewage, trade and other waste. All citizens past middle age can remember the time when there was good swimming and even fishing in most of our boundary waters. That time, however, is past, and, as to most of our shore line, at least for many years to come, beyond recall. We must frankly recognize the conditions as they are and make our plans accordingly.” Noting that it was “an undeniable fact that adequate opportunities for summer bathing constitute a vital recreational need of the city,” the release also said, “It is no exaggeration to say that the health, happiness, efficiency and orderliness of a large number of the city's residents, especially in the summer months, are tremendously affected by the presence or absence of adequate swimming and bathing facilities.”

To that end, Parks moved forward on a plan to construct wading pools for children, but officials acknowledged that it did not help adults. To remedy this, Parks invested in a massive project to build 11 Olympic–sized Works Progress Administration–funded pools in 1936 and took responsibility for the city's bathhouses in 1938. The WPA pool facilities at Crotona Park in the Bronx; Betsy Head Pool, Red Hook Park, and Sunset Park in Brooklyn; and at Highbridge, Jackie Robinson, and Thomas Jefferson Parks in Manhattan all include recreational facilities that date to 1936. Smaller centers at St. James Park (ca. 1935–37) and Williamsbridge Oval (1937) in the Bronx, Metropolitan Pool (1935) in Brooklyn, facilities at Central Park's North Meadow (late 1930s) and in J. Hood Wright Park (1935) in Manhattan and the Cromwell Recreation Center (1936) in Staten Island opened during this era. Williamsbridge Oval is interesting in that it was the site of a reservoir, and when the reservoir was no longer needed for water supply purposes, the land was transferred to Parks to develop an athletic complex—a different sort of public utility, but one just as necessary. Clearly, more than ever before, the Parks mission included providing recreational opportunities for city residents.

Expanding Options for Recreation

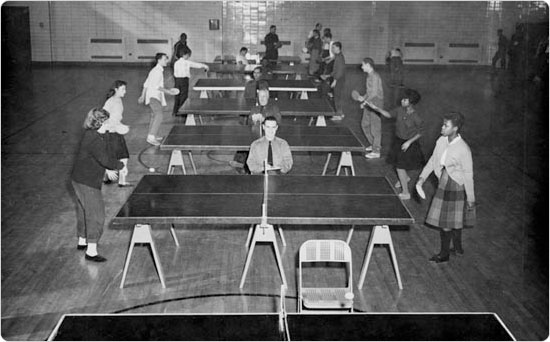

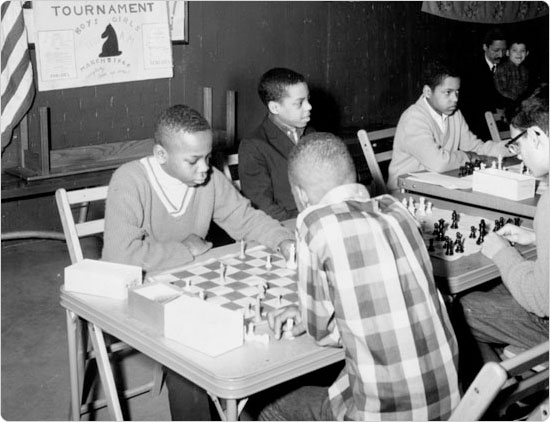

For years, City officials had agreed that recreational opportunities helped ameliorate social ills, especially among youth. By the 1940s, recreation was fully integrated in the Parks mission. At the beginning of 1946, Parks officials noted that children played checkers, handball, horseshoe pitching, jacks, paddle tennis, and shuffleboard, and participated in table tennis contests and outdoor track meets. Parks held softball and marble tournaments “in which 8,000 boys took part,” and held swimming meets “in which over 3,000 boys and girls swam.” Parks' stadium on Randall's Island hosted public and private high school and Amateur Athletic Union championship events. Over 1,300 men and women played in the annual tennis tournament, “and a like number took part in the golf tournaments which are annual events on the ten municipal courses.” “The 154 regulation baseball diamonds and 293 Softball diamonds located in the parks provided fields for hundreds of amateur baseball games witnessed by thousands of spectators who are followers of this popular sport,” a press release noted, adding that outdoor dancing was especially popular: “Over 490,000 dancers waltzed, rhumbaed, jitterbugged, and do–si–doed through a dance series which lasted all summer, and included all types of dancing.“ Parks counted an astounding 63 million visitors to the city–s six beaches, and officials noted that they were “looking forward to an enlarged recreation program in 1946, and has already set in motion a program of competitive events in basketball, boxing, ice skating, and indoor swimming.”

Providing Year–Round Fun

Parks were extremely popular with all that the department offered, but the problem remained that most parks facilities were outdoor facilities, and by virtue of the climate, out of commission for many months out of the year. So in 1946, Parks, together with the Park Association, pushed a plan to build 12 indoor recreation centers in underserved communities that would enable year–round use. Iphigene Sulzberger, the wife of New York Times publisher Arthur Hays Sulzberger, headed the Park Association committee that backed the proposal, and a Times editorial the next day noted, “It is hard to overestimate what this would mean to the boys and girls of this city, where wholesome places to play in winter are sadly nonexistent. Our huge investment in park areas should produce year–round dividends by building health and curtailing the restless idleness that leads too many times down the path to crime.”

Although the plan called for nearly a dozen indoor centers, only a few were actually built. The first, St. Mary's Recreation Center in historic St. Mary's Park in the Bronx was completed in 1951. The Opening Day Brochure, March 30, 1951 explained, “Experience has taught the Park Department that, although the park system has been greatly expanded, its present program is decidedly weak in one respect. It is based primarily on outdoor activities, and, with its present inadequate indoor recreation facilities, it can function to its fullest extent only from the first of April to the first of November. During late fall, winter and early spring, there is a decided lull in park activities and attendance falls off. There is a break in the continuity of the program, the children pick up other interests, many of them undesirable, and it is difficult to bring them back into the wholesome atmosphere of the public park system.”

The St. Mary's facility operated seven days a week from 10 in the morning until 10 at night with various activities planned for four periods a day, one in the morning, two in the afternoon, and one in the evening. The center was designed to accommodate 15,000 people a week in programs staffed by trained specialists, including gymnasium activities, swimming, manual training, arts and crafts, and cooking. The St. Mary's facility also held general use rooms for “group meetings, movies, ping-pong, music, hobbies, television, juke box, radio, billiards, etc.”

Other centers planned elsewhere included areas in which City and Parks officials determined had the largest populations of at–risk youths, including 173rd Street and Fulton Avenue in Crotona Park; St. John's Park in Brooklyn; Bergen Street and Schenectady Avenue at Betsy Head Park; Livonia Avenue and Hopkinson Avenue, McCarren Park at Lorimer and Bayard Streets; the Triborough Houses in Manhattan at Second Avenue and 120th Street; Chelsea Park at 27th Street and Ninth Avenue; Charles G. Young Playground at Lenox Avenue and 143rd Street; and Marconi Playground at 108th Avenue and 157th Street in Jamaica. A recreation center was built at St. John's Park in 1956, and a center was eventually built on the planned site in Crotona Park, but other centers fell by the wayside. In 1954, Parks added to its purview the Brownsville Recreation Center in Brownsville, Brooklyn. The facility was originally known as the Brownsville Boys' Club, and had been opened in 1953 after years of planning by a group of public–minded Brooklynites under the guidance of Abe Stark, President of the City Council of New York.

To make up for the lack of year–round sites, more playgrounds were built using playground directors. As Robert Moses noted in 1954 in the Brownsville Recreation Center Opening Day brochure, “the results we aim at are stabilizing influences on the welfare of the community, increase the value of surrounding property and above all pleasanter city living”:

The playground is a powerful weapon on so-called juvenile delinquency. To quote City Council President [Abe] Stark, “only supervised recreational centers, planned playground activities and healthy athletic competition can provide our city's boys and girls with a healthy environment. How much better it is to fight juvenile delinquency in this manner than to let young people congregate in bars, cellar clubs and disreputable honky tonks . . . What we need most is prevention, not apprehension.”

And Mayor Wagner included a note that the city's recreation program “will constitute a basic attack on our Youth Problems.”

The Department of Parks also focused on senior citizens by way of its “Golden Age Centers,” offering passive recreation to the elderly. A proposal in 1955 to build an old-age center near the Ramble in Central Park was rejected, and a contribution by the Florina Lasker Foundation withdrawn, when bird enthusiasts protested the plan. Another recreation center in Queens, Lost Battalion Hall, was assigned to Parks in 1960[EM DASH]the WPA-funded facility dated to 1939 when the two–story, 36,000 square foot building, with a firing range and drill hall was built for the Queens Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion (the Queens VFW still has office space on the second floor).

The Hoving Era

The 1965 mayoral campaign of Congressman John V. Lindsay included a now–famous “White Paper” on reforming park and recreational facilities that was drafted by Thomas P. F. Hoving (who would become Lindsay's Parks Commissioner). Commissioner Hoving's tenure was notable in that the “Department of Parks” became the “Department of Parks and Recreation,” solidifying the agency's role in the area of recreation. Among other recommendations, including a proposal for more “vest–pocket” parks, Hoving called for expanded recreational facilities and an expansion of the definition of recreation to include more cultural offerings. Hoving noted as much in his 1966 Annual Report to Mayor Lindsay:

We have gone considerably further and become the Administration of Recreation and Cultural Affairs. Recreation has been given a new status and emphasis . . .

By a series of experimental public games, happenings, giant puppet festivals, ethnic festivals such as the Oktoberfest, and mass games such as the giant Capture–the–Flag game in Central Park, we have given recreation a new definition. We have induced the public to participate in great numbers in a series of celebrations of communal life.

At the Urban America Conference in September 1966, Hoving was effusive about the role of recreation: “There is truth to the idea of bread and circus for the people. Work and relaxation are the A plus B that equals life. But the K factor—the constant—the always —is Recreation!”

Under Hoving, Parks made a concerted effort to build more recreation centers, including smaller facilities, in neighborhoods that were especially underserved. Hoving worked with the Department of Housing and Urban Development and philanthropic organizations like the Kennedy Foundation to secure additional funding for recreational facilities. Facilities acquired or built in this era included the Fort Hamilton Senior Center (1967) in Brooklyn, and the Pelham Fritz Recreation Center in Harlem's Marcus Garvey Park, which was opened in 1969—composer Richard Rodgers, who grew up nearby at 3 West 120th Street contributed $150,000 towards the cost of the adjoining amphitheater.

Continued Growth in Recent Decades

Following the economic downturn of the 1970s and residual effects that lasted for the city into the 1980s, Parks was able to redirect its energies towards building recreation centers. Asser Levy Recreation Center was updated and equipped with a computer resource center. Sorrentino Recreation Center in Queens was acquired by the City from the Knights of Columbus in 1974 and rented to the Police Athletic League until 1985 when it became a full Parks facility. A second facility, Roy Wilkins Recreation Center in Queens took nine years to open, from 1977 when the Veterans Administration gave part of its land and the hospital building on it to the City to create the center to its opening in 1986. The 1990s saw further growth: Louis Armstrong Recreational Center opened in Corona, Queens in 1995.

In recent years, however, three major recreational facilities have been built: Chelsea Recreation Center (2004) in Manhattan, the Greenbelt Recreation Center (2007) in Staten Island, and the newest, the Al Oerter Recreation Center in Flushing Meadows Corona Park (2008). These centers combine state–of–the–art features with a continuing commitment to promoting public health. These and all the Parks recreation facilities—everything from full recreation centers to community centers to field houses to nature centers—now offer a wide breadth of services such as indoor pools, weight rooms, basketball courts, dance studios, boxing rings, art studios, game rooms, computer centers, and libraries. An educational component now supplements the physical activities, and the City Parks Foundation, Parks' nonprofit partner, sponsors many free programs year round.

The facility in Chelsea was originally started in 1974, but construction was halted in 1976 because of the fiscal crisis, and the building was used to store agency records. Construction resumed in 2001, and the 56,000 square–foot facility was finished in 2004. The six–floor center includes a basketball court, arts & crafts space, a caf?, gymnasium, weightlifting and aerobics areas, pre–school classrooms, and a computer lab (an amenity early reformers could not anticipate). The six–lane 25–yard–long pool also features a mosaic dolphin–themed mural consisting of 175,000 glass tiles, donated by the Italian tile manufacturer Bisazza with assistance from the Italian Trade Commission.

In the Staten Island Greenbelt, the 18,000 square-foot facility is the first public recreation center built in Staten Island since the Cromwell Center in Tompkinsville opened in 1936. A former morgue, the landmarked Dutch Colonial–style structure features a weight room, multipurpose rooms for arts and crafts, and dance studios. Outside basketball courts, tennis courts, a soccer field, croquet lawn, and bocce courts provide other recreational options at the center.

At Flushing Meadows Corona Park, the Al Oerter Recreation Center features a cardio room, weights, an indoor racquetball court, a gymnasium, an aerobics room indoor track, and a computer resource center. Nearby, the Flushing Meadows Corona Park Pool & Rink boasts an Olympic–sized pool and NHL–regulation ice rink, including a fully ADA–accessible design. The 110,000 square–foot facility there is one of the largest ever built in a city park.

New York's ambitious PlaNYC blueprint for the city's future designates eight sites across the city as "regional parks," and Parks plans to enhance these areas with amenities that support recreational opportunities to keep New Yorkers healthy and active. Two major PlaNYC projects are in design and should go into construction in 2009—a recreation center at Ocean Breeze Park on Staten Island and the McCarren Pool and Recreation Center in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. Ocean Breeze is a 110-acre park that used to be part of an adjacent hospital campus. Although most of the park is sand dunes and wetland and must remain in its natural state, there is a large parcel of approximately 10 acres where active recreational activities can take place and plans include soccer fields, baseball fields, and the city's third premier indoor track and field facility. In Greenpoint, the readaptation and renovation of McCarren Pool and Recreation Center (closed since 1984) will revive one of the eleven pools opened by Robert Moses in 1936. The more than $50 million that has been allocated to McCarren Pool will fund the renovation of the pool for swimming, the construction of a year-round recreation center, and the preservation and restoration of the historic bathhouse building and entry arch.

For the quality and breadth of resources offered, Parks recreation center fees remain remarkably low and a bargain compared to private gyms. And as the epidemic of obesity hits urban areas particularly hard, especially among children, Parks has partnered with the City's Health Department to focus more strongly on providing recreational opportunities. The latest program, BeFitNYC uses the Parks Department website to help citizens locate activities by sport, age group, zip code, or borough. As the Parks Commissioner and Health Commissioner urge, “A world of friends, fun, and fitness waits just outside your door.”

Related Links

Indoor Recreation Facilities

BeFitNYC

Activities & Facilities

PlaNYC

Parks Photo Archive