History of Playgrounds in Parks

Find information about NYC’s playgrounds and their locations at the Playgrounds webpage.

Despite significant changes over more than a century in the equipment and appearance of New York City's playgrounds, as their designs have evolved one thing has remained constant—the essential role that the playgrounds play in the vitality of urban neighborhoods, and in particular the physical development and socialization of the city's children. Not only is a playground a place where a child may fly down a slide, soar on a swing, scale heights on a play structure, or be cooled by a spray shower, but it is also a critical part of a child's emotional education, where he or she discovers perhaps for the first time the challenges of the world outside the home. Today the Parks Department maintains nearly 1,000 playgrounds throughout the city, near schools, in large parks, or situated independently, that vary in size and appearance from tot lots to major athletic facilities.

Playground Beginnings

Several plans submitted in the 1850s for the original Central Park included various play areas, but in practice, areas for free play were restricted during the early years of the park. Central Park designers Olmsted and Vaux designated a hill in the southern portion that they called the “Kinderberg” or “Children's Mountain” for children to climb on (at the present–day Chess & Checkers House), but overall there were few formal play areas in the park. At first schoolboys (not girls) were allowed to use parts of the park for free play on certain days of the week, but the park would lack permanent equipped playgrounds for many decades.

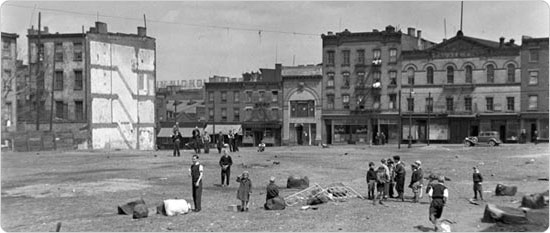

During that time, however, a period of just 30 years during the 19th century, a wave of immigration more than doubled the population of New York City, from 720,000 in 1865 to 1.8 million in 1895. Overcrowded tenement districts on the Lower East Side and the neighborhood on the west side of mid–town Manhattan known as “Hell's Kitchen” teemed with children, many of whom worked long hours in factories. Around the turn of the century, child labor laws began to improve life for many youngsters, but the only place they could play outdoors was the street, alleyways, or vacant lots. In response to these deplorable conditions, leading reformers of the Progressive era in New York City lobbied for the creation of a new kind of small park for children— the playground.

In 1884 a Tenement House Committee was appointed to study the problem, and in 1889 the Brooklyn Society for Parks and Playgrounds was organized, the first society of its kind in the state of New York. The New York Society for Parks and Playgrounds was incorporated in 1891, described as a “moral movement not a charity.” The New York Society was founded by Charles A. Stover, former Mayor Abram S. Hewitt, and Columbia University President Seth Low. The society lobbied city government, demonstrated how to use play equipment to mothers and children, and operated an experimental playground from 1891 to 1894 on Second Avenue between 91st and 92nd Streets.

The Old Ways of Play

Before the Parks Department provided recreation opportunities for children, play areas were built by private philanthropic organizations and the public education system. The earliest playgrounds, called “sand gardens” or sand boxes, appeared in the 1880s on the grounds of social service centers known as “settlement houses,” established by reformers in tenement districts. These facilities typically featured play equipment such as sandboxes and slides, as well as open space for organized games.

Play areas existed at city schools thanks to a state law passed in 1895 that decreed, “Hereafter no school house shall be constructed in the City of New York without an open–air playground attached to or used in connection with the same.” In New York, the Board of Education aimed to open at least one playground in each school district. The first two such playgrounds, no longer extant, were located at 69th Street and Broadway and 95th Street and Amsterdam. These playgrounds were open during the school year, after school hours, and early plans included opening the facilities year–round and with buildings for winter activities.

The Importance of Play

The movement to build more playgrounds got the City's official recognition in 1897, when Mayor William L. Strong appointed the Small Parks Advisory Committee with crusading journalist Jacob A. Riis as its secretary. The Committee advised playgrounds with play equipment and trained recreation specialists, designed to be a “healthful influence upon morals and conduct . . . for the physical energies of youth, which, if not directed to good ends, will surely manifest themselves in evil tendencies.” For these early reformers, recreation was not an end in itself, but was directly linked to “social morality.”

Reformers such as Theodore Roosevelt argued that play was a “fundamental need” that, if thwarted, would hamper the development of the child and might even lead to a life of crime. But even though these early playground advocates viewed play as instinctual and basic to human nature, they believed it would benefit by adult organization, one proponent commenting: “play is less systematic and vigorous without supervision.” Therefore, the activities undertaken during this era included structured activities such as marching, singing, a salute to the flag, a talk by the school principal, gymnastics, “organized free play”, drills, folk dancing apparatus work, " occupation work (known to later generations as “arts and crafts,” it included pastimes such as raffia, clay modeling, and scrap books), basketball, and “the good citizens' club.”

Playground Quotes

“If we would have our citizens contented and law-abiding, we must not sow the seeds of discontent in childhood by denying children their birthright of play.”

–Theodore Roosevelt, Hon. President, Playground Association of America

“Self government is to be learned as an experience, rather than taught as a theory. Hence in a permanent democracy, adequate playgrounds for all the children are a necessity.”

–Luther Halsely Gulick, President, Playground Association

“Much crime and most juvenile delinquency are undoubtedly the results of perverted play and recreation.”

–Playground and Recreation Association

“Play is not merely a good thing for the child; it is an essential part of the process of his growth . . . it is for the sake of play that infancy exists.”

–Joseph Lee, President Playground Association, 1916

“If our boys . . . are going to acquire the habit of subordinating selfish to group interests, they must learn these things through experience and not from books or the bleachers . . . ”

–Luther Halsely Gulick, Popular Recreation and Public Morality, 1912

Parks Plays Along

The playground movement gathered momentum, and in 1898 settlement house workers Charles B. Stover and Lillian D. Wald formed the Outdoor Recreation League (ORL). Over the next four years ORL opened nine privately sponsored playgrounds on parkland acquired by the City. In 1902 newly–elected Mayor Seth Low agreed to have the City Parks Department operate and improve the ORL playgrounds. On an October day the following year, the first permanent municipally–built playground in the country opened in Seward Park at Hester and Essex Streets on the Lower East Side. Seward Park— with improved surfacing, fences, a recreation building, and play equipment— established the basic playground design of the future. Between 1903 and 1905, nine playgrounds opened in Manhattan alone.

In 1908 the Playground Association of America noted 11 playgrounds in Manhattan and five in Brooklyn. The Seward Park, Hamilton Fish, Tompkins Square, St. Gabriel's Park, Thomas Jefferson Park, and Dewitt Clinton playgrounds in Manhattan were all “of the first rank in size and equipment” and Corlears Hook, East Seventeenth Street, John Jay, Hudson, and East River Parks were “either devoted in part only to the playground, or are not of the size and completeness of the others.” In Brooklyn there were playgrounds at Bedford Avenue under the Williamsburg Bridge, two at Greenpoint Park at Manhattan and Driggs Avenue in McCarren Park, New Lots Playground at Christopher and Sackman Streets in Brownsville, and a playground at McLaughlin Park at Bridge, Tillary, and Jay Streets near Downtown Brooklyn.

Seward Park: The First Municipally Built Playground in New York City

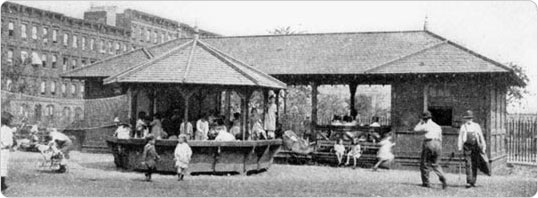

When it opened on October 17, 1903, Seward Park heralded a new era in children's playgrounds in the city, becoming a model for playground programming and design. The facility in the north corner of the park featured cinder surfacing, fences, recreation pavilion, and play and gymnastic equipment. The city had acquired the land for Seward Park by condemnation in 1897, but due to lack of funds, the site remained largely unimproved until the intervention of the Outdoor Recreation League.

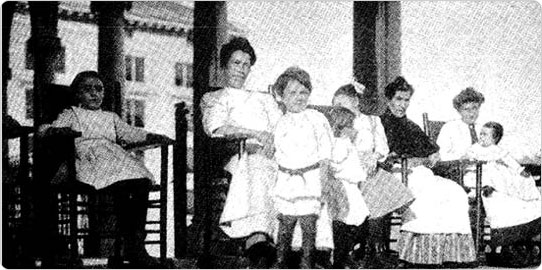

In addition to the playground, the 1903 plan for the park featured a large running track with an open play area in the center and a children's farm garden in the southeast corner. Curving paths and a north–south mall divided the park into recreational areas. The limestone and terra cotta Seward Park Pavilion was equipped with marble baths, a gymnasium, and meeting rooms. Rocking chairs were placed on the broad porch for the use of mothers tending their small children. Though few remain (except at Union Square and Columbus Parks in Manhattan, and McGolrick Park in Brooklyn), such pavilions were once a more common amenity, and could be found at De Witt Clinton, Thomas Jefferson, and Corlears Hook Parks in Manhattan, as well as Sunset Park in Brooklyn, among other venues.

A contemporary account in the New York Times reported that 20,000 anxious children mobbed the park as it opened: “At the first sign the gates were to be opened all the children present . . . acted in unison and made a rush for the approaches to the park. They swept around and through the policemen, and, without pausing, leaped over the iron fence about the playground. So sudden was their rush that it was irresistible. It took by surprise an unfortunate photographer who was just trying to get a picture of Mayor Low and knocked his camera helter–skelter.”

Pumping Up Playground Numbers

In 1910 Charles Stover, revered as the “Father of Seward Park,” became Parks Commissioner and immediately set out to increase the number of playgrounds in the city. The post of Supervisor of Recreation (under the Park board) was also created in 1910 to focus resources in the area of children's recreation. The Bureau of Recreation organized a variety of programs for city youngsters, from track meets and baseball leagues to folk dancing and children's farm gardens. The appointment of a recreation director was strongly supported by playground associations, as well as the National Highway Protective Society, which sought to free streets for vehicles rather than children's play (an attitude reversed in part by later generations with the advent in the 1960s of temporary street closures for use as Playstreets).

Interim solutions for providing more playground sites included using undeveloped city lots for play areas, opening school yards year–round, and constructing elevated play areas on the city's bridges and industrial piers. Parks reported average attendance for Manhattan and Staten Island at about 250,000 per month during the summer. Stover was so successful at redirecting resources to playgrounds that in 1911 he had to rebut allegations that he was “merely a playground commissioner” by noting that he worked to keep an athletic field out of Battery Park and strived to keep Central Park pristine.

The 1913 Report of the Public Recreation Commission noted there were 36 playgrounds in Manhattan, nine in Brooklyn, and one in Queens “and none in the Bronx or Staten Island.” The report also noted 228 facilities overseen by the Board of Education, up from 88 playgrounds and 11 roof playgrounds in 1907. These included “Indoor Playgrounds,” playgrounds for mothers and children, “Open Air” playgrounds (16 citywide41;, “Evening Playgrounds,” and “Kindergarten Centers.” By 1915 there were 70 equipped playgrounds throughout the city with features such as swings, slides, basketball frames, and seesaws. In the lingo and tenor of the time, some of the play structures were referred to as outdoor “gymnasia” and were used to conduct formal exercises.

Even though there were dozens of playgrounds across the city, it was not until 1926 that the first equipped play area opened in Central Park. At the south end, Heckscher Playground opened in one of the three areas designated for play in the original 1858 Greensward Plan for Central Park (the other two being the current sites of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the North Meadow). The playground was an immediate success, especially with children from outside the immediate neighborhood, and despite arguments against the “encroachment” to the park's design, succeeded in establishing a pattern of perimeter playgrounds at Central Park (eventually numbering 19) that were situated in a manner providing proximity to adjoining neighborhoods, while having the least impact on the original design by Olmsted and Vaux.

First Playgrounds by Borough

Manhattan: Seward Park, October 17, 1903

Brooklyn: McCarren Park, Late Autumn, 1903 - two playgrounds with outdoor gymnastic apparatus were developed; one for boys at the corner of Bedford and North 14th Streets, and one for girls at the corner of Manhattan and Driggs Avenues Vincent Abate Playground

The Bronx: St. Mary's Park, June 22, 1914 – in 1914 eight playgrounds were opened in the Bronx; two in Crotona Park, and one each in St. Mary's, Macomb's Dam, Claremont, Pelham Bay, Fulton and Echo Parks (the one in St. Mary's Park was first by about a week)

Queens: Ashmead Park, Jamaica, June 1914 (now called Ashmead Mall) at Liberty Avenue and 168th Street, it was discontinued as a playground after being seen as a traffic hazard; another playground opened in 1914 in Forest Park

Staten Island: Stapleton Playground, 1924 – unfortunately, it was unclear that Parks had formal title to the property, and it was transferred to the Department of Real Estate and sold in 1976; the next oldest park is Kaltenmeier Playground, at Virginia Avenue and Anderson Street (originally known as Rosebank Park) a “play area” existed at Westerleigh Park in 1910

The Modern Playground

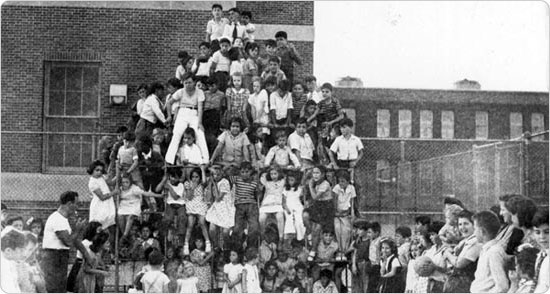

The reform spirit of the playground movement subsided after World War I, but it forever changed the perception and use of parks in America. By the 1920s, playgrounds and recreation had become established policies of parks departments all over the country. Under Commissioner Robert Moses, who served from 1934 to 1960, the Parks Department advanced the work of earlier reformers by greatly expanding the number of playgrounds in the city. During this era, space for organized play was seen as necessary for every neighborhood, and the playgrounds were intended to provide “clean, wholesome play” and to keep children off the streets, preventing both juvenile delinquency and accidental injury. Many playground openings were grand events, which in addition to the requisite speeches by public officials and dignitaries included musical, dance, and theatrical performances, and were even broadcast live on the City–owned WNYC radio station.

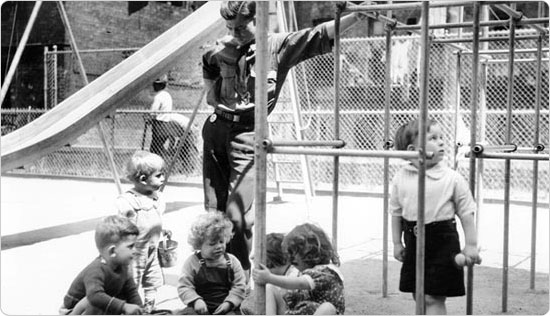

During Moses' tenure, the number of playgrounds in the city grew from 119 to 777. Many of these facilities were built during the Depression through federal relief programs like the Works Progress Administration. It was during this period that Parks Department designers created the familiar details that give “traditional” playgrounds the character they retain today. The combination of the simple brick comfort station, the wood and concrete park bench, the wire mesh trash basket, “croquet wicket” fences around lawn areas, and birdbath water fountains was a design ensemble launched in the 1930s. Other typical features of these playgrounds included large asphalted areas adorned with sandboxes, see-saws, metallic jungle-gyms and monkey bars, swing sets, and slides. They were designed for the use of a wide age group, from small children to those of early adolescence. In addition, new playgrounds were staffed by recreation specialists who led organized games for children.

After World War II the City found innovative ways to acquire and develop playground sites. Beginning in 1938, the Board of Education agreed to provide land next to schools where the Parks Department could build and maintain Jointly Operated Playground (JOPs). The Parks Department also built scores of recreation facilities as part of public housing projects. The greatest sources of new sites were arterial highway projects. Broad right–of–ways acquired for new parkways and expressways in the 1940s and '50s provided thousands of acres for playgrounds and other recreation facilities, which were often built with funds provided for road construction.

Playground Definitions

What is a playground may seem obvious today (generally a separate parcel with play equipment), but in the early years of playgrounds, there was debate over what constituted a “playground.” The 1910 Annual Report for the boroughs of Manhattan and Richmond noted that “[t]he term 'playground' like the term 'park' has even yet an indefinite meaning. It is necessary to make careful distinction between the following different types of play centers, all of which, though widely differing in purpose and use, are grouped nevertheless under the term 'playground.'” The report goes on to list five categories; the type of playground that most approximates our current conception of playground is the “girls' playground):

- Athletic Fields: for young men and boys over 14, the equipment consisting of gymnasium frames, basketball courts, running tracks, jumping pits, and tennis courts. “In every case lockers, toilets, baths and water are essential and a seating stand desirable.”

- Baseball Fields: equipment for which being a backstop, the “screening of adjacent windows within the danger zone” and bleachers.

- Boys' Playgrounds: for boys under 14, they contained swings, see saws, slides, basketball frames, and a “platform or open space for general games.”

- Girls' Playgrounds: for girls under 16 and boys under 8, they are the same as boys' playgrounds except that there was more space for free games and added sand boxes, small swings, and “baby hammocks for the very small children.”

- Midget Playgrounds: for children under 4, the features for such playgrounds included sand piles, small swings, and hammocks.

Playground Innovation

In the 1960s the Parks Department experimented with new types of play spaces and innovative designs. One initiative was the introduction of modest quarter-acre playgrounds (and community gardens) called “vest pocket” parks that were placed in densely built neighborhoods where larger sites were unavailable. They were often situated mid–block, encompassing no more than one to three building lots.

Another innovation was adapted from the “adventure playgrounds” of England and Scandinavia, where children themselves created play forms in vacant lots with surplus construction material. Similar experiments were conducted in New York and helped inspire designs for novel climbing structures, catwalks, swing ropes or tire swings, and other new playground features. Architect Richard Dattner designed several such playgrounds in Central Park and another example is Manhattan's Highbridge Park.

The Adventure Playground emerged from movements in 1960s Europe that worked to reclaim derelict urban spaces, many caused by the devastation of World War II. Filled with trash and debris, the sites were considered unfit even for parking cars and were therefore abandoned by developers. Children, on the other hand, seemed to have few if any qualms about these forbidden sites, and often played happily in rubble heaps, seeming to prefer the informality of dirt and scraps to formal jungle gyms.

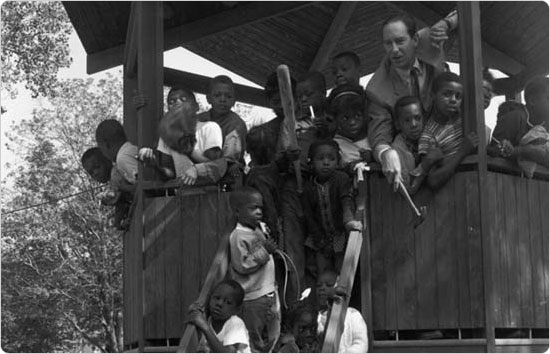

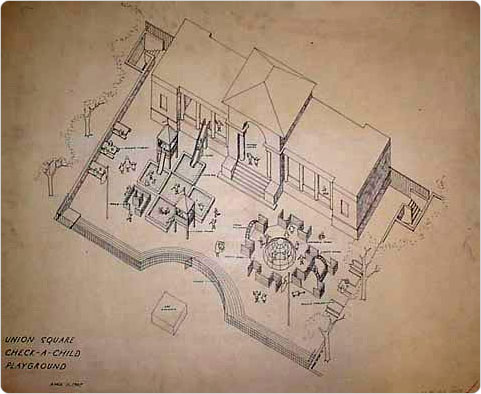

Check–a–Child Playground

The “Check–a–Child” playground, designed by Richard Dattner, was a short-lived experiment in government sponsored day–care. It was launched in 1967 in Union Square—the Parks Department announced it as a place where “harried mothers intent on hunting bargains” were able to “park their youngsters for a few hours of solo shopping”—the state–of–the–art playground was shoehorned into the submerged area in the park's northern region and was funded through the support of local businesses intent on revitalizing Union Square. Parents could leave their children in the custody and supervision of Parks Department workers for the fee of 25 cents for the first three hours.

Adventure Playgrounds Proliferate

Adventure Playgrounds sprouted up in locations all over the New York, predominantly in Manhattan, but though the sites more often contained innovative play forms and configurations, they did not make use of raw building materials as in their European counterparts (federal safety standards may have stifled the use of alternative materials, and the potential for lawsuits inhibited total improvisation).

The new layouts updated the 1930s playground's repertoire of metal swings, jungle gyms, and sandboxes. New ways of thinking about play space became fashionable, with prominent architects such as Louis Kahn and Isamu Noguchi proposing designs for Riverside Park. Adventure playground builders designed with natural materials to integrate the play area into the land itself. The playgrounds were muted in tone and blended structural building materials such as cast concrete with natural materials such as ropes and large–size timbers.

By the 1970s, as playground safety rose in importance, many playgrounds were retrofitted to eliminate hazardous conditions such as hard surfaces and the potential for long falls. With Adventure Playgrounds in particular, many parents began to worry about the possibility of injury in the tunnels and massive play shapes that blocked visibility of their children at play. Some sought to remove altogether the 1960s designs—finding the aesthetic, especially the liberal use of concrete, to be brutal, harsh, and un–park–like, while others thought these designs created arenas for imaginative play. (Preservationists of modernism would later rally to save all or part of these latter–day “landmarks,” especially those by leading designers.) Over time, these playgrounds were replaced by more colorful catalog model equipment with less sand and fewer moving parts.

Accessible Playgrounds

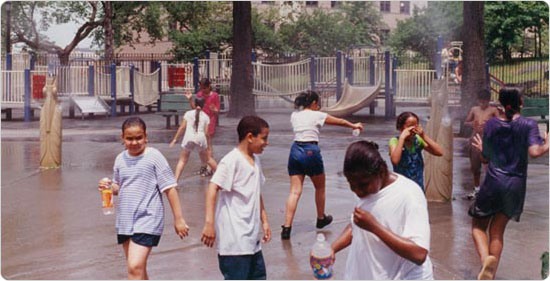

Another modern priority was to make playgrounds more accessible to disabled children. In 1984, the first fully accessible playground in the country opened in Flushing Meadows Corona Park in Queens. The Playground For All Children included an interpretive trail of trees and flowers marked with Braille plaques, a race track and suspended bridge that accommodated wheelchairs, and swings and seesaws that children operated themselves by pulling on chains. The Playground For All Children was notable in that it engaged both disabled and able–bodied children, and served as a prototype for similar facilities elsewhere. Parks collaborated with the Department of City Planning, architects, and community and advocacy groups for the disabled on its design and construction. Built to accommodate children using crutches, canes, walkers, or wheelchairs, the playground also provided opportunities for social, cognitive, sensory, and motor activity. Its features included ramped play equipment, ground level play features, accessible swings, and wheelchair-accessible tables and drinking fountains.

Today there are six Playgrounds for All Children in New York City parks: Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx (2000) Central Park's Bendheim Playground (1997), Playground 70 (2003) and Vesuvio Playground in Manhattan (2007); Flushing Meadows Corona Park in Queens (1984); and Bloomingdale Park on Staten Island (2006). In addition, Playground 70 in Manhattan was constructed in partnership with Boundless Playgrounds, a nonprofit group that assists communities in planning fully accessible playground facilities.

Tailoring Playgrounds to Neighborhoods

Since the 1980s, many of the Parks Department's playground designers have responded to the local culture, geography, and history of their neighborhoods, and often include elements bearing a relationship to the name or position of a particular playground. An example of this can be seen at J. Hood Wright Park in Upper Manhattan, where the playground equipment was custom designed to resemble the George Washington Bridge, which is visible from the park's high vantage point along the Hudson River. Brooklyn Bridge Park Playground takes advantage of the park's waterfront setting by incorporating appropriate nautical motifs—the climbing equipment is embellished with decorative sails and a sandbox is shaped like a boat. In Manhattan's McNair Park (named for Dr. Ronald Erwin McNair (1950–1986), the African–American astronaut who died aboard the Space Shuttle Challenger), the play equipment features a space motif—and is arrayed around a central lunar–like play sculpture.

Commissioner Henry J. Stern (served 1983–1990; 1994–2001) directed his designers to introduce where possible animal–inspired play sculptures and decorative features in playgrounds built during his tenure with Parks.

Imagination Playground

Playgrounds have even gone on the road: The Rockwell Group's mobile “Imagination Playground in a BOX,” devised by David Rockwell takes up the concept of unstructured, child–directed “free play” and places Imagination modules in sites across the city for a short time (several months) in each location (much like the peripatetic “Floating Lady” pool barge). Designed to complement traditional playgrounds, the Imagination modules provide a flexible armature for many types of play versus prescribed activities. Reminiscent of a treasure–filled trunk, the Imagination kits open to reveal a variety of loose parts such as foam blocks and sand and water tools, as well as found items such as tarps, fabric, and milk crates.

In May 2009, the City and Rockwell Group broke ground on a permanent flagship site at Burling Slip in Lower Manhattan that brings together the three key components of the Imagination philosophy: an open multi–level space with sand and water features, a huge array of “loose parts”—or toys and tools—and trained on–site staff who will maintain and manage the site. In addition, Rockwell Group has funded an endowment to ensure that the Imagination Playground will carry out its intended function for years to come.

Watch a video about Imagination Playground in a Box

Today and Tomorrow

As New York City rebuilds its recreation facilities, playground designs continue to evolve in response to maintenance experience and community needs. Parks Department landscape architects and consultants are making playgrounds safer, easier to maintain, and most of all, enjoyable for children. Although much has changed in the 100–plus years since playgrounds debuted, one thing remains the same: The City and the Parks Department are committed to providing safe places for children to experience healthy and positive play.