History of Bicycling: A Revolution in Parks

Find information about biking and greenways at the Bicycling and Greenways webpage.

Bicycles have been a fixture in parks across the city since their invention and popularization in the late 19th century when “velocipedes” and unicycles evolved into “high–wheelers” and “tricycles” and finally bicycles.

Bicycling Takes Off

The bicycle craze in the late 19th century caused Park officials to quickly develop guidelines for this relatively new and growing pastime. For instance, in Brooklyn in 1885 the Parks Department promulgated new rules and regulations for bicycles, and its annual report noted that the “use of the bicycle and tricycle for recreation and exercise has considerably increased in Brooklyn. The park and parkways have afforded exceptional facilities for riding. The tricycle as a vehicle for ordinary exercise and pleasure riding is more generally used than last season. This machine is greatly used abroad as a convenient means of traveling about the country, and would be found very serviceable, especially for adults, for that purpose upon the park and parkways and upon the quieter roads and byways in the rural neighborhoods of the adjoining county towns.“

Bicycle riding was allowed in Prospect Park and at Coney Island all the time during the November–May off season and before 10 a.m. and after 7 p.m. other times of the year. In establishing the new regulations, the Parks Department worked with local riding clubs, “with the view to avoid all possible opposition from the public, and secure comfortable means and opportunity for a desirable recreation.”

The “wheelmen” were required to register with the Parks Department and get a badge to wear on their chests at all times. (The 1885 Annual Report notes that the Central Park Board of Commissioners also issued bicycle badges.) The Parks Department had arrangements with bicycle clubs such as the Long Island Wheelmen, Kings County Wheelmen, Brooklyn Bicycle Club, and Bedford Cycling Club.

The report continued, “Generally, wheelmen must avoid as far as possible all cause for complaint; they must observe due care and caution at all times, especially in the vicinity of pedestrians; they must conform promptly to all directions and cautions from the keepers and other officers of the park, and in case of accident render such assistance as may be necessary, give their name and address, or badge number, if required, and assume such responsibility as circumstances may warrant.”

Parks officials in this era also permitted, indeed encouraged, bicycling on Ocean and Eastern Parkways, and on the Coney Island Concourse. However, administrators stressed safe riding behavior, and the regulations stated that owing “to the large amount of driving upon the roadways, riders must observe great care in order to avoid the possibility of accident.”

1885 Brooklyn Parks Department Bicycle Rules and Regulations

By John Y. Culyer, Chief Engineer and Superintendent:

The use of the bicycle and tricycle for recreation and exercise has considerably increased in Brooklyn. The park and parkways have afforded exceptional facilities for riding. The tricycle as a vehicle for ordinary exercise and pleasure riding is more generally used than last season. This machine is greatly used abroad as a convenient means of traveling about the country, and would be found very serviceable, especially for adults, for that purpose upon the park and parkways and upon the quieter roads and byways in the rural neighborhoods of the adjoining county towns.

There have been few accidents chargeable to carelessness or inexperience in the handling of bicycles, and the riders themselves, as a body, are solicitous to observe every precaution calculated to ingratiate themselves, as riders, in the good opinion of the public. The following rules and regulations have been approved by the Commissioners and meet in a practical way all the requirements which, from my observation and experience, it seems to be necessary to impose upon riders:

Rules and Regulations for Bicycle and Tricycle Riding

In Prospect Park, and upon the Parkways and Concourse at Coney Island.

Prospect Park

From November 1st to May 1st riding will be permitted upon all the pathways, subject to the following and such other restrictions as the comfort and safety of pedestrians may demand.

From May 1st to November 1st the pathways may be used before 10 A. M. and after 7 P. M. At other times no riding will be permitted upon the pathways, except on those south of the lake, from the Irving Statue to Gate 4, and to Lookout Hill.

The west drive, running parallel with Ninth avenue, Fifteenth street and the Old Coney Island Road to Gate 4, or the southerly entrance, may be used at all times.

Care must be observed in crossing the plazas at the entrances to the park.

Bicycle riders must dismount and walk down Ravine Hill and Deer Paddock Hill at all times.

Tricycle riders may descend those hills mounted, provided they apply their brakes and go slowly.

No blowing of whistles or bugles will be allowed.

All riders must carry lighted lamps after sundown.

No fast riding, speeding or racing will be permitted, nor will coasting be allowed under any circumstances. This is not intended to prevent tricycle riders using foot-rests instead of pedals when applying brakes and going down hill slowly.

Keep to the right as a rule, and always be prepared to give timely warning to pedestrians.

Parkways and Concourse

Riding at will upon the ocean and eastern parkways, and the Coney Island Concourse, subject to the usual rules of the road, will be permitted at all times.

Owing to the large amount of driving upon the roadways, riders must observe great care in order to avoid the possibility of accident.

Conform generally to the rules prescribed for the riding in Prospect Park.

The foregoing privileges are subject to the following conditions:

All wheelmen will be required to register their name and address at the office of the Chief Engineer and Superintendent, Litchfield Mansion, Prospect Park, and procure a numbered badge, to be provided by the Park Commissioners, which badge shall be worn conspicuously on the left breast, and no wheelman will be permitted to enter the park or go on the parkways and concourse without such badge. They will otherwise conform to such rules and restrictions as may from time to time be established and imposed by the chief engineer and superintendent.

The New York wheelmen who hold badges issued by the Central Park Commissioners will be permitted to ride upon Prospect Park, &c., under the same conditions as govern the Brooklyn wheelmen. Visiting wheelmen may secure temporary permits to ride on the park and parkways on personal application at the office of the Chief Engineer and Superintendent on Prospect Park. Particulars as to time and place for making application for such permits may be had at the Chief Engineer and Superintendent's office in the park. Generally, wheelmen must avoid as far as possible all cause for complaint; they must observe due care and caution at all times, especially in the vicinity of pedestrians; they must conform promptly to all directions and cautions from the keepers and other officers of the park, and in case of accident render such assistance as may be necessary, give their name and address, or badge number, if required, and assume such responsibility as circumstances may warrant.

Special privileges, such as parades, entertainment of visiting clubs, &c., may be at all times arranged for, by timely application to the Chief Engineer and Superintendent.

The members of the Long Island Wheelmen, Kings County Wheelmen, Brooklyn Bicycle Club and Bedford Cycling Club, may co-operate in securing a strict observance of the foregoing rules and regulations in such manner as may be arranged, to the satisfaction of the Chief Engineer and Superintendent.

The object of these rules and regulations is to serve the interests of bicycle and tricycle riders generally. They have been approved by the most experienced riders, and were, in the main, suggested by the organized clubs of this city, with the view to avoid all possible opposition from the public, and secure comfortable means and opportunity for a desirable recreation.

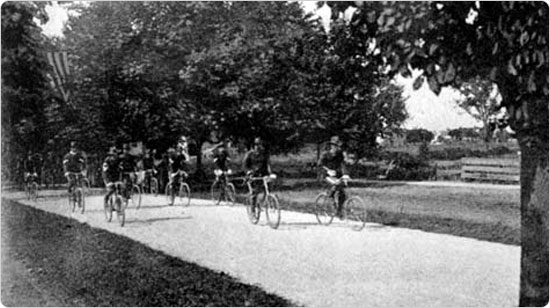

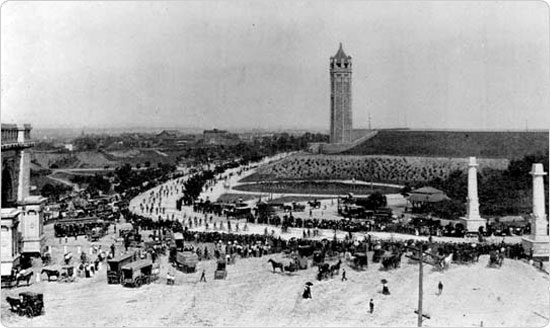

Blazing the Way for Bike Paths

On June 15, 1894, thanks to the efforts of Albert H. Angel of the Good Roads Association and other sports enthusiasts, Ocean Parkway became the home of the country's first bike path. More than 60 wheelman clubs from the New York and New Jersey area, as well as bicycle police, were on hand for the opening ceremony. Since racing was still a concern, cyclists were limited to speeds of 12 miles per hour on the bike path and 10 miles per hour on the parkway. That said, bicyclists were allowed to race in controlled settings.

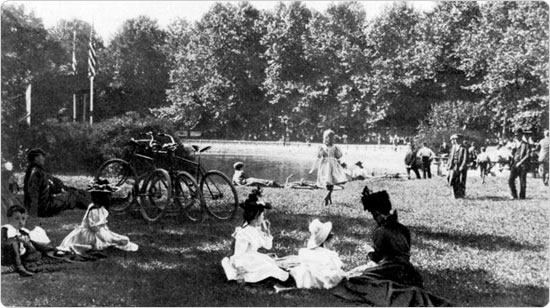

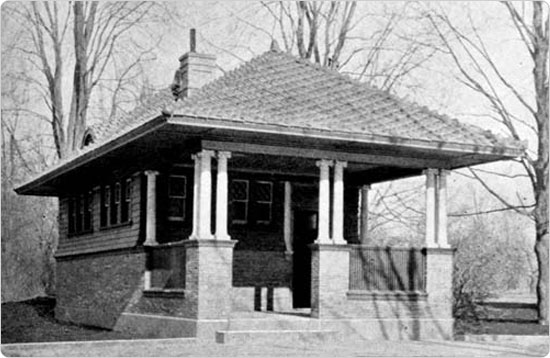

In 1896, the Brooklyn Parks Department built bicycle racks and shelters at Prospect Park to accommodate cyclists. Also in 1896, Prospect Park hosted "one of the most interesting parades of the year" when the Chinese Viceroy Li Hung Chang visited the park wearing a peacock feather and yellow jacket with Brooklyn Mayor Frederick W. Wurster and Union League Club President William Berri and other dignitaries, and the entourage was escorted by citizens on bicycles.

Pedal Progress

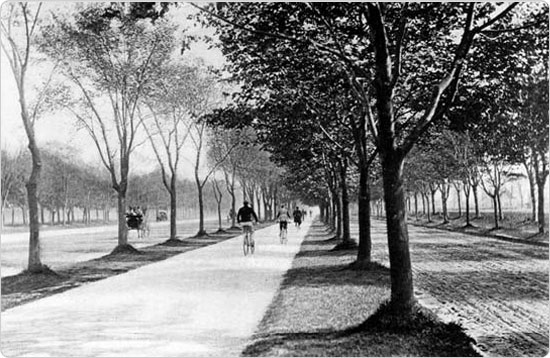

Although bicycling fervor had diminished somewhat by the close of the 19th century, the Parks Department continued many bicycle initiatives. Bicycle paths were created along Pelham Parkway in the late 1890s. The picturesque ride along Riverside Park and Drive, with its views of the river and palisades in the distance, proved so popular that despite a motion brought before the Parks Department to ban biking from the park (evidently some felt the activity an intrusion at this scenic location), bicycle racks were requested at the Grant's Tomb promontory.

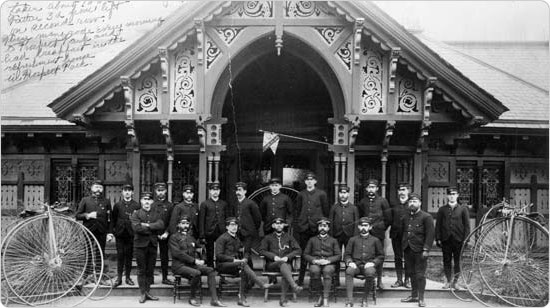

Parks also discovered the practical use of bicycles in Prospect Park and Central Park, which both produced bicycle patrols in the 1900s and 1910s (decades later, in 2000, Ford Motor Company donated fifteen electric semi-motorized "Th!nk" bicycles to the Parks Department for Parks Enforcement Patrol officers to use in large parks such as Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx and Rockaway Beach in Queens).

And for a devoted core of athletes, parks served as the site of bicycle meets and races: the Long Island Wheelmen sponsored bicycle races in the 1920s at Victory Field in Queens' Forest Park, the Century Road Club of America held races on the running track at McCarren Park in Brooklyn, the Empire City Wheelmen conducted a series of Sunday morning races on Ocean Parkway, and the Amateur Bicycle League of America used the Dreamland parking lot at Coney Island.

Shifting Gears Under Moses

In the 1930s, motivated by the dual mission of public safety and public health, park officials renewed the commitment to building bicycling facilities in parks during an era of park expansion and new recreational opportunities championed by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses. In 1936, the Parks Department opened the defunct drive west of the Mall in Central Park to bicyclists and called attention to the need for more bicycling areas, “to meet the growing demand for this form of recreation.” “Bicycling is not only popular with growing boys and girls, thousands of mature men and women derive pleasure from this form of exercise,” a press release noted. “The use of City streets and boulevards for bicycling is dangerous to the bicyclist and the use of walks in the parks dangerous to the pedestrian.” The area west of the Mall in Central Park was resurfaced and lines were painted separating bicyclists and roller skaters.

Bicycling was an integral part of the New Deal work relief projects of the 1930s and 1940s. The Moses administration planned bicycle paths using WPA funds along the Harlem River Speedway, in Hillside Park in Queens, along the center strip of Pelham Parkway in the Bronx, and down Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn. The agency also included bicycle paths in Riverside Park in its 1937 WPA–funded expansion and allowed cyclists to use running tracks.

Bicycle races were held on the newly opened WPA–funded facility at Randall's Island. And Moses' ambitious WPA–funded Belt Parkway circumferential road, completed in 1940, featured 31 miles of waterfront bicycle paths that ran through Brooklyn and along the Shore Parkway, treating cyclists to a panoramic view of New York Harbor as hardy riders embarked on an eastbound path that eventually led to quiet marshes far away from the hustle and bustle of city life.

A Parkway Pushes Advancement

Parks' embrace of bicycling in the early days of the Moses administration is exemplified by the opening of the Long Island Motor Parkway as a biking path. The path in eastern Queens, meandering through Kissena, Cunningham, and Alley Pond parks, was originally built in 1908 as a racecourse by the railroad mogul and financier William K. Vanderbilt, Jr. (1878–1944). The Parkway later developed into a major public thoroughfare— the first high-speed route from Queens to Suffolk County— one of the first concrete roads in the nation and the first highway to use bridges and overpasses. By World War I, the completed 48-mile, privately owned Parkway was open to the public as a toll road, used primarily by New York City socialites travelling to their summer estates on Long Island.

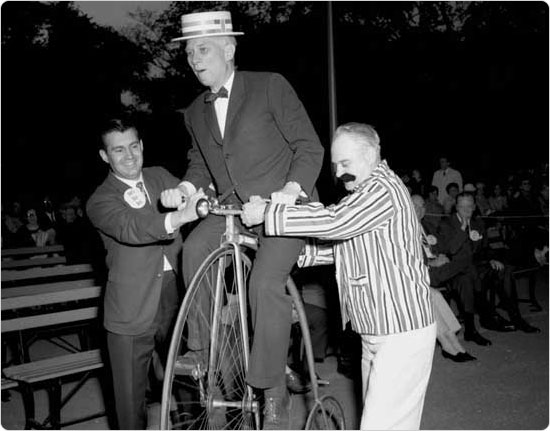

The road fell out of favor when the free Northern State Parkway was developed in 1929, and had to shut down in April 1938. Three months later, Moses transformed the Queens section of the Parkway into the Queens Bicycle Path. The first two and–a–half mile section opened in July 1938 for the exclusive use of bicyclists. Commissioner Moses appeared at the ribbon cutting with Otto Eisele, President of the Amateur Bicyclists of America, after which hundreds of bike riders rode down the Parkway. The event featured historic bikes and trick bicycle riders.

The Long Island Motor Parkway bicycle path kicked off a push by the Parks Department to build nearly 60 miles of bicycle paths in the city's parks. Commissioner Moses wrote to Mayor Fiorello La Guardia that although the bicycle craze had diminished from its peak at the end of the 19th century, the 1930s had seen “a revival of interest in the old–fashioned, but now somewhat streamline, bike.”

The routes of various lengths Moses originally proposed were located in 21 parks across the city, from 9.5 miles of routes in Brooklyn's Marine Park to a .13 mile path in Soundview Park in the Bronx. Moses wrote, “We have planned winding layouts which will lead in most cases from somewhere to some other place, and of such length and design that there will be no feeling of monotony to a person who rides his or her bicycle with the intention of securing mental relaxation and physical exercise; and also that the sport can be indulged in with reasonable assurance of safety.” The 1939 post–World's Fair plan for Flushing Meadows envisioned eight miles of bike paths and a rental concession at the Meadow Lake boathouse, noting that “the mild topography and interesting landscape will make bicycle riding particularly enjoyable.”

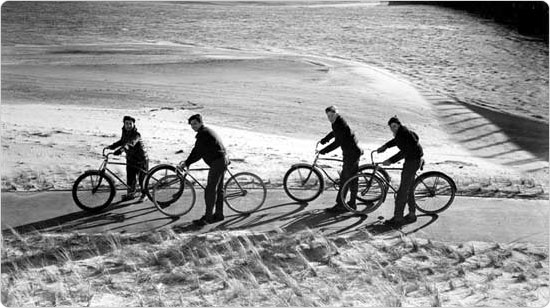

Seated Among Recreational Options

By the 1940s, bicycling had an established position alongside other recreational activities in the pantheon of park offerings. A press release from 1944 noted, “In the case of bicycling, the sport has risen in the past few years from comparative obscurity into the spot it holds to–day as one of the most popular forms of outdoor recreation.” By that year there were 29 bicycle paths in the parks, the largest of which were located at Central Park in Manhattan, in Prospect Park and along the Belt Parkway in Brooklyn, in Van Cortlandt Park and along the Hutchinson River Parkway in the Bronx, in Alley Pond Park and along Cross Island Boulevard in Queens, and in Silver Lake Park in Staten Island. The boardwalks at Coney Island in Brooklyn, Rockaway Beach in Queens, and South Beach in Staten Island were also open for bicycling until 1:00 p.m. Monday through Fridays and until 11:00 a.m. on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays.

By the 1950s, the Parks Department had succeeded in building 50–plus miles of bike paths in city parks, and because of the popularity of cycling competing with other uses of park thoroughfares, officials felt obliged to restrict bicycles to designated paths. Park regulations then stated, “No person shall ride a bicycle, velocipede or scooter in any park, except in places designated for such riding; but persons may push such machines in single file to and from such places, except on beaches and boardwalks.”

The Need for Speed

The Parks Department also made a provision for cycling competitors. The Siegfried Stern Kissena Park Bicycle Track, New York City's only public bike track, was built in 1963 and named for bicycle enthusiast Siegfried Stern, treasurer for Hartz Mountain Products and benefactor of many Jewish organizations. An annual junior cycling race, sanctioned by the Amateur Bicycle League of America, was founded in his honor when the track was named, and in September 1964 the track was the scene of the United States Olympic Team trials. Today the velodrome is known in the cycling community as the “track of dreams.” The facility was rededicated in 2004 after two years of work that updated the 400–meter track into a sleek, state–of–the–art cycling facility. During the renovations, new asphalt pavement was added, finished with a special acrylic seal coat, as well as new landscaping and trees, bleachers, a custom–designed perimeter fence, regulation racing lines, and a new drainage system.

Taking It to the Streets: New Cycling Opportunities

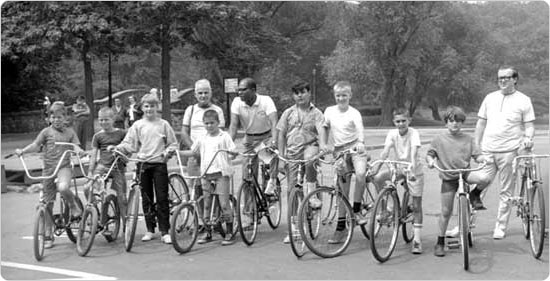

As cycling again grew in popularity during the 1960s, and there was an increased interest in environmental issues, Parks began experimenting with closing parts of its larger parks to cars and hosting bicycling events. In 1966 the Parks Department started a pilot program in Prospect Park to bar vehicles during summer weekend hours. In 1967 Parks hosted a “Cycles in Fashion” bike night in Central Park sponsored by Best and Company department store that highlighted bicycling accessories. The event also kicked off once–a–week closings of the park to motor vehicles during the evening hours.

The Parks Department also expanded drive closings to include Forest Park in Queens and Silver Lake Park in Staten Island. Proposals for bikeways in all five boroughs emerged in 1968, ideas that came to fruition in the 1970s. The city under Mayor Lindsay also experimented with road closures in the early 1970s that closed portions of thoroughfares such as Madison Avenue to automobile traffic on weekends, granting limited exclusive use to bicyclists and pedestrians (in 2008 the administration of Mayor Bloomberg revived this tradition on a trial basis, closing Park Avenue to vehicular traffic on four consecutive Saturdays in August.)

In 1974 in Central Park, Parks hosted a “Bicycle Bash” sponsored by Pepsi–Cola to kick off the spring–summer bicycling season. Jack Natriboff— “Jack the Bicycle Clown”— led a parade through the park. Also in 1974 the City experimented with Sunday closings on a four–mile stretch of the Grand Concourse in the Bronx. The Grand Concourse closings continued into the 1990s, and in 2006 Bronx Borough President Adolfo Carrion, Jr. restarted the effort, adding a specific health focus that featured tips on healthy eating, health screenings, and power walks.

Financing Fun, Safety, and Fitness

As subsequent mayors and park commissioners kept up these bicycle–friendly initiatives, by the mid–1970s, some concrete examples of municipal support also emerged. The City proposed spending $1.6 million for a bikeway program in 1976, and in 1977 established a Bicycle Advisory Committee to strengthen lines of communication between city government and the bicycling community. In 1978 the first bike lanes were created: the southbound lane traveled on Broadway between Central Park South and 23rd Street, then Fifth Avenue to Washington Square (3 miles), and the northbound lane went up Sixth Avenue between 8th Street and Central Park South (2.5 miles).

The City also experimented with bike lanes on the Queensboro Bridge in 1978. A Prospect Park bikeway also debuted in 1978. In 1979, the Department of Transportation established a federally funded Bicycle Safety Coordinator position that raised awareness of the presence of bicycles on the city's streets. Parks also hosted bicycle races, tours, and bike–a–thons. One such event on May 1, 1977 had bicyclists making eight laps around the Central Park drive— a distance of 50 miles. In 1979 a Blue Ribbon Panel appointed by Central Park Administrator Elizabeth Barlow and Parks Commissioner Gordon Davis made recommendations to significantly extend park drive auto traffic closures in Central and Prospect Parks, and these changes took effect on May 1. As Commissioner Davis commented, “People will be the rule, and cars the exception.”

Greenways Get a Go

As advocacy groups such as Transportation Alternatives became a vocal constituency in the 1980s and 1990s, the start of the new millennium saw a renewed commitment to this bicycling. That, coupled with the accelerated transformation of the city's post–industrial waterfront to parkland and recreational use, led to a boom in “greenways” and bikeways around the city, especially Manhattan.

After hundreds of years of various uses, from docks to railroads to industrial development, the effort to create continuous bike routes has been a complex process requiring coordination between numerous governmental agencies with varying and at times overlapping jurisdictions. When it comes to the waterfront, city, state, federal, and private interests are all stakeholders, and waterfront sites often are served by several city agencies, from the Department of Environment Protection to the Economic Development Corporation to the Parks Department itself. The original circumferential Greenway Plan for Manhattan dates to 1993, and much of the work has since been completed, so that today one can ride nearly uninterrupted on a Greenway from Dyckman Street in Upper Manhattan, down to the tip of Battery Park, and around the east side of the island all the way up to 34th Street.

Bridging the Greenway Gap

Manhattan's Riverside Park has evolved greatly since 1875, when Frederick Law Olmsted first completed his design for the park. The park was expanded by fill at the waterfront in the 1930s, providing an area adjacent to the water for active recreation extending from West 72nd Street to 155th Street along the Hudson River. For more than seventy years, however, one of the only missing links on the west side existed in a section of Riverside Park from 83rd to 91st Street, where Robert Moses' Henry Hudson Parkway makes a scenic sweep towards the waterfront, and the bike and pedestrian path gets edged out.

For decades the Parks Department sought a solution to this problem and after years of planning and taking into consideration the environmental impact, Parks is constructing a “Riverwalk,” a bridge structure over the river that will close that final gap on the west side of Manhattan. The $13.3 million project broke ground in 2007 to link the park between 83rd and 91st Street using a pile-supported platform in and along the Hudson River. $300,000 of the funds for the project came from a federal Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act grant.

The Bronx and Beyond

The ideal of bike travel as a means not only to connect people and places inside the city but beyond as well makes the Bronx New York City's most important bike frontier, simply because it is the only borough connected to mainland. Five different Greenways do or will connect to Westchester County from the Bronx, and from there hundreds or even thousands of miles beyond. Today the Pelham Greenway leads riders in to Westchester County where the East Coast Greenway Alliance has provided a bike route all the way to Maine.

In Van Cortlandt Park, the future Putnam Rail-trail exists today as a dirt path, which connects to the already complete Greenway in Westchester that continues for many miles. Parks plans are now in the works to pave this old train line and connect it to a future path all the way up to 230th Street. Parks has completed a design of the Hutchinson River Greenway, which will also connect cyclists to a planned path in Westchester, but the masterpiece of Greenway design is the Bronx River Greenway. Running through the heart of the borough, the Bronx River Greenway project has been a labor of love for more than 30 years. The very last leg that approaches the Westchester County line has already been built, and many different parks projects are in the works to connect the various riverside parks properties into one string of pearls.

In Queens, Parks has spent the last ten years restoring the Greenway that Robert Moses actually built originally in his 1939 Shore Parkway project. The original highway, with two car lanes in each direction, grew to three lanes and thus swallowed up the bike paths that at one time also ran east and west alongside the cars. Parks' modern day plans involved unearthing (sometimes literally) the former eastbound path on the south side of the Shore Parkway and making it a two–way, continuous ride from Knapp Street in Sheepshead Bay to JFK Airport. Already we can boast a smooth scenic ride up to Erskine Street in Brooklyn. Construction of the leg to 84th Street in Queens should begin soon. Parks planners have already started designing the pathway to the air train in JFK, along with the help of our friends at the Port Authority, who recently took on the mantra of Greenways for themselves. When people realized they could be saving “green” by being “green,” they came to the old Green experts at NYC Parks.

Riding Toward the Future

In 2006 the City's Department of Transportation implemented a three–year plan to mark 200 miles of on–street bicycle routes, a key initiative of PlaNYC. The agency also sponsored guided bicycle rides during Bike Month in May 2009. In addition, DOT publishes the useful bike maps that show bike routes across the city. The increased commitment of the City in providing a safe network of biking routes demonstrates the adaptation of a nineteenth century pastime to 21st–century needs and priorities. Although bicycling started out as principally a leisure pursuit of the wealthy, it has evolved into a major movement that has the potential to fundamentally alter our living patterns. Whether you use your bike on occasion for fun or pleasure or cycle as your main mode of transportation, at the Parks Department and the Department of Transportation, wheels are turning in an increasingly broad effort to support bicycling in New York. As Mayor Bloomberg's PlaNYC notes, bicycling is an environmentally friendly and space–efficient way to travel around the city. And as stewards of our environment, New York has and will continue to embrace cycling as an emission–free, low–cost, and environmentally sustainable mode of transportation that also happens to promote a healthy lifestyle. What could be better?

Bonus Images

Further Reading

The Bicycle Blueprint: A Plan to Bring Bicycling Into the Mainstream In New York City, Michele Herman, principal author, Charles Komanoff, Jon Orcutt, Project Directors, David Perry, Design Director, published by Transportation Alternatives, New York, 1993.

Bike Cult: The Ultimate Guide to Human-Powered Vehicles, David Perry, Four Walls/Eight Windows, New York/London, 1995.

Related Links

Bicyling & Greenways

Department of Transportation Bicylists Page

Transportation Alternatives

Kissena Velodrome

Vanderbilt Motor Parkway